Dragon Age: Inquisition players are still struggling to import their world states despite the issue being flagged to BioWare and EA over a week ago. Regardless of what platform you’re playing on, it seems some players can only see default world states. EA community manager EA_Shepard acknowledged the issue on the official forums 10 days ago, saying the team was “aware and investigating”. Shepard also validated another issue, this one with the Golden Nug, which goes AWOL mid-playthrough or disappears entirely for some. To see this content please enable targeting cookies. Manage cookie settings Dragon Age The Veilguard Review: The BEST Bioware Has EVER Been! (Spoiler-Free).Watch on YouTube Revealing that they “reported this [to the studio] at the end of the week last week and checked up on this”, EA_Shepard recently confirmed that it was “still an open issue” and the team “is still working on this one”. The issue has apparently been further compounded by some players getting confused “around the world state importing into their game”. “When you import your world state, it will say default world state. The name does not change,” Shepard explained. “When you want to import a world state, rename it in the Keep first, import it in the Keep, and then start a new game,” they added, acknowledging that when they tried it themselves on PC, PS5, and Xbox Series X, only one was successfully imported. Shepard also confirmed that there “are ways to try to get it resolved by manually choosing the options and creating entirely new world states after you sync and replay the keep”, but acknowledged this “has not worked for all players”. Towards the end of the week, Shepard shared a further update. “Wanted to let you know I am still looking out for this one,” they said. “I know the whole ‘we are working on it’ message gets old. Believe me, I get it! There is a lot happening and being worked on with Dragon Age so things are a bit slower on other fronts. I am watching it closely though so I have not forgotten about the community!” “I get that Veilguard support is prioritised at the moment since it’s a brand new game, and Keep has always been kinda buggy, but I think I speak for all of us when I ask that this issue be made more of a priority,” said one player. As for Dragon Age: The Veilguard? Eurogamer’s Robert Purchese had a lot of good things to say about BioWare’s latest Dragon Age in his five star review. “From head to toe, wing to wing, The Veilguard is exquisitely realised and full of sophistication across systems and storytelling,” he wrote. “It’s warm and welcoming, funny and hopeful, gentle when it needs to be, and of course it’s epic – epic in a way I think will set a high bar not only for BioWare in years to come but for role-playing games in general.”

Category: Bird view / Isometric

Auto Added by WPeMatico

I love World of Warcraft, but I wish Blizzard would stop looking backwards

How is it that the most exciting thing about Warcraft in 2024 is old Warcraft games from the mid 90s? I can’t have been the only one watching the Warcraft Direct broadcast this week hoping for a glimpse of the future, and of something new – to hear what director Chris Metzen has been doing since he returned to think about the future of Warcraft a year ago. Instead, all we got was remastered versions of Warcraft 1 and 2, and Classic servers for World of Warcraft Classic – Classic Classic – and a tease for player housing in WoW. That was as good as it got: player housing, which, admittedly, is exciting, but it’s still a niche development for a 20-year-old game. How many people, besides WoW players, are excited to hear about WoW expansions in 2024? They have become as predictable as winter.

Ironically, all the Warcraft Direct did was remind me how exciting Warcraft used to be, which I know is partly the point of a 30th anniversary broadcast, but isn’t it also about setting up what’s next? We used to hang on Blizzard’s every word, eager to see what it had been making for us. Warcraft 1, Warcraft 2, Warcraft 3 – the latter rewrote the rules of the RTS. Then of course there was World of Warcraft, which really did seem to captivate the world. But how long has it been since it can claim to have done that? It’s telling that the most exciting thing to happen to WoW in recent years was the launch of Classic, five years ago. The future seems to have become about reliving the glory of the past.

It’s not just Warcraft that’s tiring. Look across Blizzard more broadly and ask, “When was the last time it gave us something new?”, as in actually new, not Warcraft Rumble new. Diablo 4, as much as I enjoyed it, wasn’t much of a surprise. Do we really have to go back to Overwatch in 2015 to find the answer?

What a renaissance moment for Blizzard productivity that was. Finally, as if freed from a kind of perfectionist paralysis, not one but two experimental and unfinished games were released: HearthStone and Overwatch. Both were enormous, company-changing successes, and they seemed to usher in a new age, one of creative transparency, as well as a willingness to try things and, perhaps, fail. Where did that go? HearthStone, as we were repeatedly reminded during the Warcraft Direct, is now 10 years old, and Overwatch is unironically having a Classic moment of its own, reinstating 6v6 play in a call-back to the game’s original launch. Where is the new?

Look, I know none of this exists in a vacuum and that Blizzard has had more on its plate than creative concerns in recent years. It was embroiled in allegations of workplace misconduct for years, and trapped in web of will-they, won’t-they Microsoft acquisition complications for just as long. Then, it was rocked by layoffs. Clearly, life at the studio hasn’t been easy, and I have every admiration for the people who’ve stuck it out and are the new face of Blizzard, and who’ve turned out games like Diablo 4 and the World of Warcraft expansions we see now. Evidently a lot of really important structural work at the company has been done. The Blizzard we’re presented with in showcases now seems more diverse, and the dialogue between game teams and their audiences feels more natural and open than ever before. Detailed road-maps lay out the path ahead, blogs detail upcoming features in depth, and videos document changes and design philosophies in ways Blizzard never used to do. There’s also experimentation and risk being taken on existing projects. Vital progress has been made.

But when is Blizzard going to excite us with something new again? It’s as though, in being tossed around a bit, the company lost some of its nerve. In clinging to former glories in the way it does, it comes across as shackled by them, because no matter how exciting a World of Warcraft expansion gets – or a trilogy of them, as we’re getting now – it’s never going to make the game as exciting as it once was, in that moment when it first arrived, when it was new. Reliving it over and over again in Classic isn’t the same thing. It’s true of Hearthstone and of Overwatch too – there’s no escaping the diminishing returns; there’s only so much excitement one game idea can naturally give.

Perhaps this is the curse of extraordinary live game success, an eternal clinging to a previous high and reluctance to do anything that might upset the audience and recurring paycheck. But for how long is that sustainable? When you’re pulled in several directions by several games, where do you find the time and creative space to do something new? Moreover, where do you find the desire and the appetite to take the risk?

What’s doubly worrying is that Blizzard does seem to have been trying. That “brand new survival game” set in a “whole new universe”, codenamed Odyssey, sounds like it was exactly the kind of ‘new’ I’m talking about. But it was canned – canned after six years of development amidst Microsoft-mandated layoffs earlier this year. It’s as though the suits came in, saw the risks involved, and only the risks, and thought better of it. Better to have a nice stable income from tried and tested brands instead. A rumoured StarCraft shooter led by former FarCry boss Dan Hay doesn’t sound anywhere near as interesting by comparison; it’s an idea Blizzard has been toying with for decades – remember StarCraft Ghost?

It’s a shame. Blizzard has produced some of the games I remember most fondly of any that I’ve played, and I’ve no doubt there’s the talent there to make more of them – to give us experiences we haven’t even conceived of yet. But does it want to? That’s the question. In looking to the past, it’s in danger of living in it and being hemmed in by its own success. I don’t want Blizzard to become a Greatest Hits band; I want to hear something new.

Beastieball gives Pokémon an Into the Breach-style sports twist, and I can’t get enough of it

After the gentle ramblings of Wandersong and the contemplative care package that was Chicory: A Colorful Tale, one of the last things I expected developer Greg Lobanov to make next was a Pokémon-style sports tactics game. But here we are regardless, and cor, I think Beastieball might be what I’ve been looking for in a Poké-like ever since my love for Pokémon proper began to wane around the Black and White era. I’ve dipped my toes back into the Poké pool more recently, of course, but I don’t think my love for it now will ever be as strong again as it was back when I was a rabid 10-year-old playing Red and Yellow on my Game Boy. Partly because I’m a recovering Pokédex completionist and I just can’t put myself in that kind of position again, but mostly because the innovations Pokémon’s tried to introduce in more recent entries have all fallen a little flat for me.

It’s a feeling that’s pushed me into trying other Poké-likes over the years. Your Cassette Beasts, Coromons and TemTems and the like. But Beastieball – even in its current early access form – already feels like the pick of the bunch. And it’s all thanks to its 2×2 volleyball pitches.

The setup of Beastieball is winningly familiar to classic Pokémon. You, a small-town Beastieball liker, must set off on a quest to become to number one Beastieball coach so you can gain enough fame and influence to save your home’s Beastie reserve from being bulldozed for a honking great stadium. You must travel from town to town beating other coaches in their definitely-not-gym-style arenas, engaging in good-natured games with other, err, not-trainers along the way and growing your team with newer, more powerful Beasties as you go. Not by catching them, you understand, but by recruiting them and offering them ‘jerseys’ for your team, which you can only do once you’ve researched their recruitment condition – deal over 100 damage in a single shot, say, or buff a stat twice in one match – and performed that condition in battle to sufficiently impress them.

It’s a great sports-y twist on the whole endeavour, and this extends to the three core types of Beastie, too – you’ve got your Body-focused ones who like to hit the ball, for example, while others are Mind-focused and better at performing volleys. The third prong to this triangle is your Spirit-focused Beastie, who ‘likes to power up’ with stat-boosting buffs (the names for which are also quietly very good as well, with sweaty, shocked, stunned, tough and tired in the mix to name just a few). Your Beastie’s attack and defence stats all correlate to this trio of Mind, Body and Spirit, too, though currently it’s a little bit harder to work out which Beasties fit into what category based on their looks alone. This can lead to some surprise thrashings every now and again, but the good news is you don’t lose cash or progress if you suffer a defeat – you can simply try again when you’re ready. Which is pretty nice!

The best bit about Beastieball, though, is the matches themselves, which all take place on volleyball courts that seemingly spring up from the ground as soon as you bump into a wild Beastie. It’s kinda daft, but I do also kinda love it. Each side of the net is split into a 2×2 grid, into which you can field two Beasties while the rest of your team hugs the backline, ready to be tagged in whenever they’re needed. Teams take turns to attack and defend, the former phase giving you three actions to play out, but just one during the latter. And goodness me, you better make that defensive move count, because if your Beastie gets ‘wiped’ by the incoming attack, the other team score a point, and if you leave a column or row open and that’s where the ball lands? The other team also score. And it’s quite possibly the most thrilling tiny tactics game I’ve played in ages.

The way you need to have your bases covered and be thinking two, three steps ahead really reminded me of playing Into the Breach with Beastieball – though unlike Subset Games’ brilliant tactical roguelike, you don’t get to see what your opponent’s going to do in advance, giving each turn a frisson of wild and unpredictable energy. Just like in real sports games, I suppose (though disclaimer: I’ve never been one for field games much, as I spent most of my youth in the swimming pool). Still, it livens up Pokémon’s basic concept of double battles to no end, as you not only need to think about how to best use your Beastie’s respective attacks, but also where they’re positioned – as some moves can only be made in certain positions, and attacks are stronger (and defences weaker) when you’re up close against the net. The risk-reward is perfectly pitched, and it makes every match feel fresh and exciting. I also just like how moves are called ‘plays’ and can be swapped in and out of your Beastie’s repertoire at any time. Sports!

The script (and the game more generally) is very thoughtful in that way – which doesn’t really come as a surprise at all after Lobanov’s exceptionally sensitive work on Chicory. For example, I love how when Beasties are close to evolving, they suddenly get a bit awkward and sensitive, sweating profusely (draining their stamina in the process), and generally being a bit despondent. ‘Their bodies are going through some big changes,’ you’re told, and to just hang in there and give them a little extra support while they work things out. Similarly, when two Beasties play together often, their friendship can eventually bloom into ‘partners’ and then ‘besties’, letting them perform special combo attacks when they’re both in the field. They’ll also gain new ideas for moves of their own watching their teammates, giving moves a really organic and inspiring sense of cross-pollination.

Each Beastie is so gosh darn expressive, too, from their general demeanour and match animations to the way they’ll spontaneously perform some keepy-uppies if you kick them a ball out and about, or let out colourful emoji reactions during a match when their teammate pulls off a good move (which feels doubly rewarding as their coach choosing those moves in the first place). Some are, admittedly, still a little work in progress. Beastieball is currently only in early access after all, and you’re warned up front that there still might be some placeholder art in various places, including some of the Beasties themselves. But what’s here is still incredibly generous – there’s the entire story campaign, for starters, and you can play against folks online, too. Even the ‘reserve’ Beasties you’ve recruited who aren’t in your main team of five can act as your Away Team, too, appearing in other players’ games and gaining experience at the same time.

It’s all exceedingly good and promising stuff, and it’s backed up by Lena Raine’s lively and toe-tapping score as well. I’ll certainly be playing a lot more of it in the months to come, because I’m telling you now, The Breakfast Detectives and I have a good thing going on here, and I really want to be the very best, like no one ever was.

The anatomy of a scare: how do games frighten you?

Imagine you’re standing in a hallway in a game – what does the scene need in order to make it scary? Should we turn the lights off? Should we have a door where you can’t see what’s behind it, but you can hear something behind it? Should there be a threat somewhere, lurking nearby? Is music important? And at what point is it okay to spring a noisy surprise on the player? In other words, what are the rules of fear?

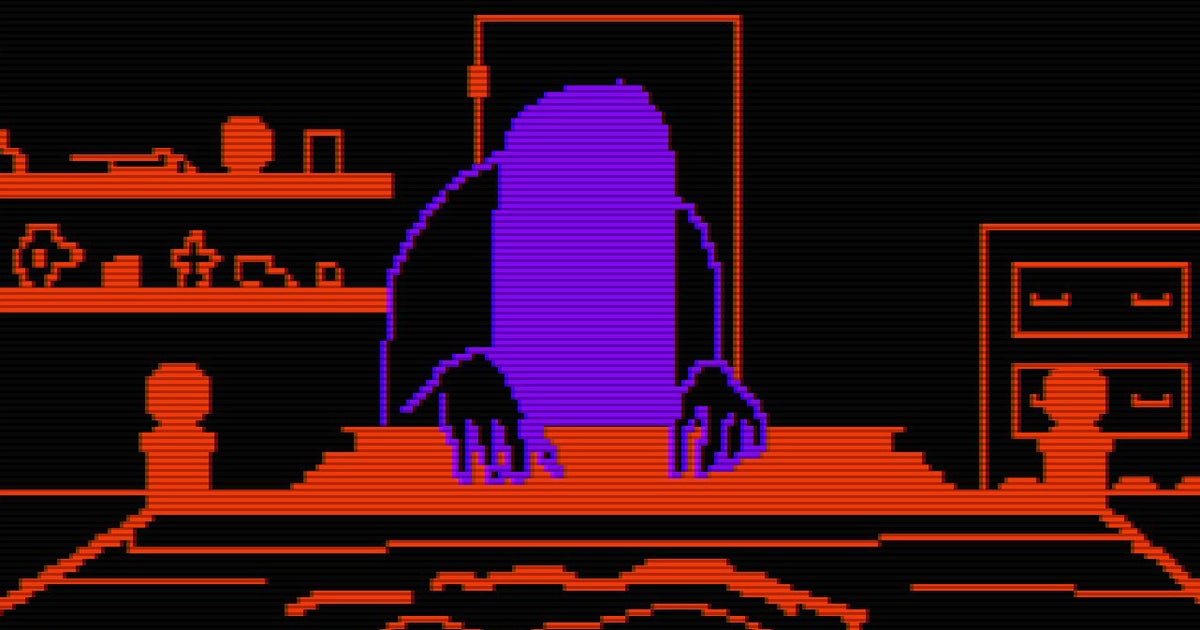

I’ve been thinking about how games scare people ever since lo-fi horror game Faith: The Unholy Trilogy scared me a few years ago, which isn’t a remarkable feat because I’m a scaredy cat. But what surprised me about Faith was how it achieved that feeling, and how little it achieved it with. Here was more or less an 8-bit game, with tiny wriggling sprites and a handful of colours, and it evoked in me the same kind of fear other blockbuster games sometimes struggle to. How was it doing it?

It mystified me enough that I asked Little Nightmares creator Tarsier about fear shortly afterwards, but though the conversation was good, a broader explanation still eluded me. Scaring people remained a magic I couldn’t quite understand, which is when, coincidentally, an answer of sorts came to me.

Magic: just as I’d once asked bright minds from games what magic meant to them, so I would ask scary-game makers how they scared people. Is there a science to it, a formula for fear, and does it change according to the game you’re making? What is the anatomy of a scare?

I sent my ravens out and here are the answers that came cawing back.

Silent Hill creator and Slitterhead director Keiichirō Toyama

Silent Hill is one of the founding series of survival horror, so there are few people who have done more for it, arguably, than Toyama. He also directed the Siren series of horror games, before co-founding studio Bokeh, which recently released Slitterhead.

“In short, I would call it the ‘stimulation of imagination’,” Toyama tells me. “The psychological appeal of horror, I believe, lies in a fundamental desire to collectively identify and overcome threats that surprise and challenge life (and species). Therefore, once something is understood, it may still be a threat, but it no longer evokes fear (as with plagues, for instance).

“Utilising this psychology, I think the key to horror as a creative genre lies in controlling the sense of understanding that is within reach but not quite graspable. A recent work that embodies this mechanism exceptionally well, though not a horror title per se, is Subnautica. It does this very effectively.”

Faith: The Unholy Trilogy creator Mason Smith, AKA Airdorf

Faith is the horror game that prompted this article and lives rent-free in my head, disturbingly. It’s a horror styled like an old Apple 2 game, and though the first Faith game was released in 2017, a third game and trilogy bundle was released in autumn 2022, when I came across it.

“Our reaction to horror is very subjective,” says Smith, “but there are some universal fears I think all humans possess: fear of the unknown, fear of darkness, things like that.

“For me, it’s important to lay down an effective atmosphere, so for games this means creating a setting where the geometry, textures, lighting, soundscape, etc. are ripe for putting the player in the ‘mood’. Once you prime the player psychologically, there are all sorts of fun strategies you as the designer can employ.

“My favourite is something I borrowed from the designers of Dead Space (2008): prime the player to be scared by one specific thing, for example a monster that you see from far away or on a security monitor or on a child’s drawing. The fun part is keeping them in a sense of dread – they know the monster is coming but they don’t know when or where or how. It can be a matter of seconds, minutes or hours before it happens. Tease little visual or audio cues – little bits of environmental storytelling – along the way. The scare – the payoff – can come suddenly in the form of a jump-scare if you want. The problem with a lot of jump-scares is they come without context, but using this method the player is already familiar with the scary thing, so when the scare finally pays off they can go ‘okay, that’s fair’.”

Still Wakes the Deep creative director John McCormack

Still Wakes the Deep is the spooky 1970s oil rig adventure that was released by The Chinese Room this year.

“With Still Wakes the Deep, our intention was to ground the player in realism, comfort and mundanity, then slowly remove the safety nets to expose natural human phobias which would create a general atmosphere where scares would be effective. We give the player safety in numbers through their crewmates, the comfort of the routine of working life and the relative protection of this impossible steel structure against the elements, after which we carefully planned out a cadence of removing those basic protections.

“We take away the crew to give monophobia, then switch off the lights to give us nyctophobia, we force them into unnatural spaces to create claustrophobia as well as vertigo, we compromise the structure of the rig to produce thalassophobia and, of course, we bring aboard a nefarious entity to ramp up the fear of the unknown and death.

“Even with all of these triggers in place, it would only work if the player felt viscerally connected to the main character, to feel everything he feels, to know his past and present and determine his future. Dan Pinchbeck, the lead creative director and writer of the game, provided a fully realised protagonist who reacts authentically to the dangers he is forced to face, and the right mix of script, sound and voice acting was essential in making the player feel everything we wanted them to feel. And because we made the whole experience from this particular character’s perspective, this naturally took away the comfort of knowledge and placed the character in situations where he isn’t sure what to do, what this thing is and if there’s even a chance he’ll make it out alive. All combined, we hoped to create a grounding in character, location and phobias where even the sound of a tin of spam hitting the floor would cause the player to flinch.”

Madison director Alexis Di Stefano

There are people who cite two-person indie horror Madison as one of the scariest games in recent years. It tells the story of a teenage boy with a camera whose pictures connect this world and that of the dead. Say cheese!

“There are many kinds of horror, different ways to create it, and various ways that impact the audience,” director Alexi Di Stefano says. “People with thalassophobia can’t handle games that plunge them into the ocean, just as people with a fear of heights might avoid climbing in VR! For me, something that left a deep mark at a young age was a game called Clock Tower: The Struggle Within. That game introduced me to something new, or at least new to me back then, and it made me feel something I never thought I could experience: fear within my own home.

“The game takes place in an ordinary house (at least in the first chapter) where terrifying events unfold. For example, you might come across a corpse floating in a bathroom tub, or an arm on a tray in the dining room. To nine or 10-year-old Alexis, that experience translated into a terror that lingered every time I walked down the hallways of my own home at night – or entered the bathroom and saw the shower curtain closed! It was terrifying but incredible; it was the push I needed to follow this path which ultimately led me to dedicate myself to horror.

“Homes are supposed to be our sacred places, our refuge, and that game showed me the opposite. Unlike most games of that era, which took place in hard-to-access locations like schools at night or hospitals, Clock Tower: The Struggle Within brought horror into an ordinary, everyday space.

“For me, the perfect scare starts with anticipation”

“When I work on the scripts for my games today, I’m very mindful of how to introduce the specific type of horror I want to convey. It’s not just about jump scares, it’s about crafting an atmosphere that unsettles players even when nothing obvious is happening, or, even more powerful, when players turn their consoles off but still can’t hake the feeling.

“For me, the perfect scare starts with anticipation, followed by tension – so much tension it feels like it will never end. It’s a raw and almost painful kind of tension that frightens more than the scare itself. This buildup is what really gets under players’ skin, making the experience stay with them long after they stop playing.

“I don’t follow a strict formula but I’m aware of a detail that, to me, is far from minor: what isn’t seen is often scarier than what’s placed directly in front of the player. The build-up is key; it’s about keeping players in a constant state of anxiety. In Madison, I play with lighting, pacing and interactivity within the environment to keep them guessing. They know something is coming but not when or how. By crafting a relationship between the player and the environment, every shadow or subtle movement can feel like a potential threat, creating fear through what’s suggested rather than what’s shown.

“A major moment I consider is when the player starts feeling fear, and it’s rarely when they expect it. In my games, I like to create scares that linger in the player’s mind, the kind that make them hesitate before turning a corner or opening a door. To me, the scare isn’t just in the immediate shock, but in the lasting anxiety it leaves behind.

“I’m fully aware that what terrifies one person may not affect another in the same way, but regardless of these differences, we always pour a lot of love and passion into what we create, knowing that people will experience it in diverse ways. If there’s one thing that’s certain, it’s that our bodies – physically and mentally – will unmistakably let us know the exact moment fear begins to take hold and when we start to surrender to it. That’s the magic of horror: it’s personal, visceral, and impossible to ignore.”

Dredge studio co-founder Nadia Thorne

As a horror fishing game, Dredge is unlike many of the other games here, yet it manages to evoke an unsettling and tense atmosphere all the same.

“One thing we observed early on while playtesting Dredge,” Thorne says, “was the power of ‘tell, don’t show’. Even in our early prototype, having characters warn players to return before dark or hint at horrors in the fog had players imagining all sorts of things that could happen to them if they were caught out on the water still when night fell.

“You can’t string players along forever and do need to deliver on the promise of terrifying encounters or you’ll lose their trust, but in Dredge the player’s own mind can be just as suspect as some of our characters.”

Dead by Daylight senior creative director Dave Richard

Dead by Daylight is a four-versus-one multiplayer horror game inspired by slasher films of the ’80s and ’90s, in which you can play as both the killer and the victim. Today, eight years after launch, more than 60 million people have played it and it’s adapted dozens of horror licences from around the world of movies and games.

“Fear is at the basis of what we do, of what Dead by Daylight is and how it came to be,” says Richard. “There are two main facets to fear: being scared and scaring people, and those are the two tenets of Dead by Daylight, which makes it unique in the horror video game universe. In DBD you can feel both helpless and extremely powerful, and both emotions are strong and make for an intense, thrill-seeking playing experience. There are innumerable types of horror – slow burn, psychological, slasher… – and Dead by Daylight delves into all of them.

“For each new chapter we release, we start with a theme,” Richard goes on, “either of horror or a type of experience we want players to feel. From there we elaborate on our vision. The whole DBD team is really passionate and everyone comes up with ideas and concepts throughout the development. Each discipline adds to the horror experience, from the visuals who inspire the audio, to the audio who inspires the VFX. Everything is connected.

“The way we know that we have accomplished our goal starts internally when we run playtests and we hear, or see, our colleagues jump or grunt in disgust – we know we’ve hit our target then. Ultimately fear can be entertaining, and that’s what we want our players to experience.

“There is no secret formula to Dead by Daylight’s success,” Richard adds. “I believe we have been very lucky to create something in which players can act out the fantasy of being the villain in a horror movie or can experience the thrill of being chased, or can just spectate on this very good raw show of humanity and emotions. Our goal is always to surprise, and I think we’ve accomplished that. Fear is the gateway to so many emotions, and we want our players to feel them all.”

Signalis writer/director Yuri Stern

Stern apologies that they didn’t have time to formulate, as they put it, a more satisfying answer, but they did have this to say about five-star banger of a survival horror game, Signalis.

“For Signalis, we focused on horror stemming from oppressive systems, both in gameplay and narrative, rather than direct scares, so the ‘anatomy of a scare’ extended for us into all aspects of the game, including the gameplay systems (restrictive inventory, dwindling resources), world-building and narrative (overbearing bureaucracy, cosmic horror).”

Bloober Team director/designer Wojciech Piejko

Wojciech Piejko worked on Bloober’s memorable sci-fi horror detective game Observer, and its early PlayStation era-inspired survival horror The Medium, and is now co-directing Cronos: The New Dawn, a survival horror set in an alternate reality version of 1980s Poland.

“Our goal at Bloober Team is to create horror experiences that linger in the minds of our players even after they have put down their controllers,” Piejko says. “To achieve this, we need to get into their minds because the scariest things don’t happen on the screen, they are happening in players’ heads. In horror, less is more. The less you know, the less you see and the scarier it becomes. Think of the first Alien movie: it’s good because you can’t see exactly what the Alien looks like so your brain starts to work. The oldest fear in the book starts to haunt you – the fear of the unknown. In my opinion, the key is not to provide too much information to the player and slowly build up the atmosphere, delving into the story while never revealing everything. There are things that should never be explained; isn’t it more interesting and even strangely romantic?

“As the horror creator, you also need to know how to control the tension, and of course, it all depends on the game you are making. Can the player fight the monsters? If so, you need to understand that when combat starts, the player feels relief – the player no longer thinks about what is lurking in the shadows and the survival instinct takes over. The key to success in this case is to create a great atmosphere and build-up before combat encounters begin, or even trick the player into thinking that they will be attacked and then not do it.

“Example scenario: Imagine you are playing a survival-horror game and looking for a key. You enter a new area and hear the rhythmic sound of something hitting the wall. Finally, you see a monster banging its head against the wall. It doesn’t see you; you have already fought this type of monster, and it’s strong and challenging so you sneak behind its back. You search the rooms and find the key, so now it’s time to pass the monster again. On your way back, you hear the banging again but this time, it suddenly stops. You check the corridor and the monster is gone. Where is it – will it jump out at you from another room? This is where the real fear starts.

“Many horror games strongly rely on jump scares, which are often perceived as the cheapest way to scare the audience. However, if done right and not too often, they can serve as a good way to bridge scenes and relieve tension, giving you an opportunity to build it up again. While making The Medium, a game with no combat, we included one big jump scare just to inform players that this type of thing may happen again, so they will be afraid for the rest of the game. To pull off a good jump scare, you need to grab the player’s attention on something else and then suddenly attack. It’s like a magic trick that can be described in three steps:

- The Pledge – The magician shows you a card and hides it in the deck.

- The Turn – The magician lets you check the deck, but you can’t find the card there.

- The Prestige – The magician pulls the card out of your pocket.

“Now let’s translate this to the jumpscare:

- The Pledge – You hear scratching coming from behind the door.

- The Turn – Despite the tension, you enter the room to find out it’s only a rat.

- The Prestige – You turn around to see the monster standing behind you.

“Sometimes, you can use only two steps; the most important thing is to focus the audience on something and then attack when they don’t expect it. Find something that the player does constantly and feels safe about, then use it against them. One of my favourite moments in making Observer was a bug that scared me to death. I was testing one of the levels and when I turned around, I saw the Janitor, who shouldn’t be there – I almost jumped out of my chair. That was a bug that spawned the Janitor in the wrong position, but it was so effective that we used this scenario in a different part of the game.

“PS: Don’t forget about the music or the absence of it – ambience and sound effects are some of the most important ingredients for evoking fear. PPS: Remember that less is more? It also also applies to graphics: darkness is your friend. Add some grain and the shadows will start to move – or did something move in the shadows? I could talk for hours but I need to go back to work on Cronos; I hope it will scare the shit out of you after its release!”

What surprises me about these answers is that I didn’t expect there to be such a close relationship between magic and fear. I’ve set out on two separate occasions to find answers to two seemingly separate topics, but discovered they are, at their foundation, perhaps fundamentally the same. They both revolve around the unknown. Magic is the term we tend to give something we don’t quite know how to explain, when we’re reaching for something our lack of understanding doesn’t let us find. That gap is important; it’s the allure. We hunger to know what’s going on so we’re no longer adrift or unmoored, our mind grasping for any explanation it can hold onto. The door in our imagination opens up and a tornado swirls through, full of anything and everything, fact and fiction, exciting ideas and frightening ones. It’s uncomfortable; we need to know.

It’s this desire Silent Hill’s Keiichirō Toyama references trying to prolong when he talks about “controlling the sense of understanding”. What he’s saying, I think, is that the player should never know, not entirely – the doorway to their imagination should always be open. Bloober’s Wojciech Piejko shares a similar viewpoint, saying, “the less you know, the less you see and the scarier it becomes”, and Madison’s Alexis Di Stefano agrees: “What isn’t seen is often scarier than what’s placed directly in front of the player,” they say. It’s scary because of your imagination: that’s the element that stays with you long after you close the game. Nadia Thorne and the Dredge team realised a similar thing: that it was more effective to hint at horrors than explicitly display them. And while Dead by Daylight seems to take a more direct approach, is it not the unknown behaviour of the player taking on the role of the killer that keeps it feeling so eternally fresh? We don’t know what they’re going to do, we don’t know where they’re going to be, and that unsettles us. It’s as Faith’s Mason Smith says: “There are some universal fears I think all humans possess,” and fear of the unknown is one of them.

After all, what better thing to help scare you than your very own mind?

After The Veilguard’s secret post-credits scene, where does Dragon Age go from here?

We’re in the endgame of Dragon Age lore now. In The Veilguard, we come face-to-face with legends that are – who are – thousands of years old, implicated in mysteries we’ve been speculating about for 15 years, since the series began. The new game openly discusses long-held secrets, and it’s thrilling, but in doing so it also uses some of them up, raising the question of where the series goes from here.

In this article, I’m going to look at what’s left to uncover as well as speculate about what might be next for the series as a whole, so fair warning, there will be spoilers – spoilers about the ending of The Veilguard and discussion of secrets revealed within. To reiterate, in bold lettering, there will be spoilers, so please don’t read this if you’re not ready for them.

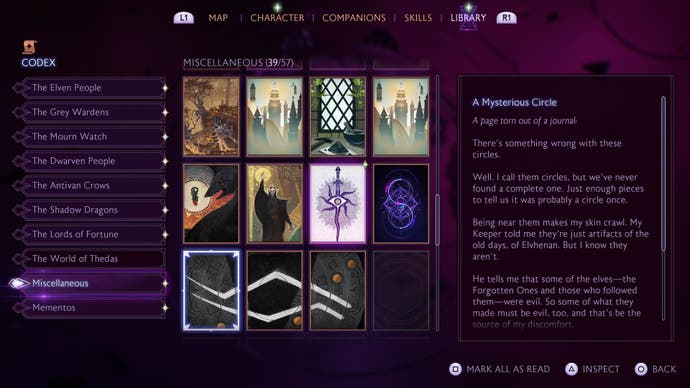

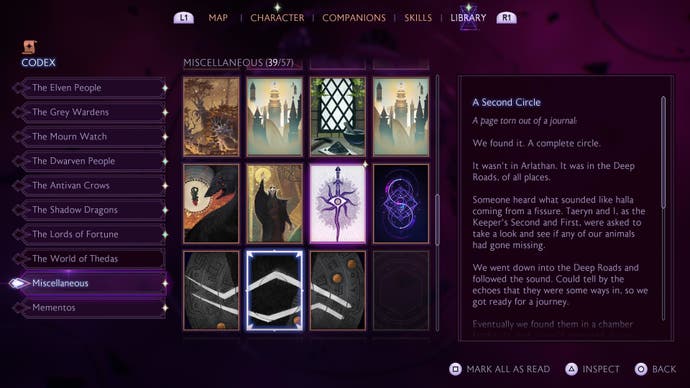

I’ll start with something that’s not necessarily a spoiler in its own right, however, and that’s the secret post-credits ending scene, which you unlock by collecting three Mysterious Circle artefacts from around The Veilguard world. The scene doesn’t actually reveal events from within the game, so is relatively safe to watch, and it gives the clearest indication of what BioWare intends to do with Dragon Age next.

In the scene, we’re introduced to what I assume will be the big new villain of the series, because remember, we’re now lacking one. But it’s not a villain we’re particularly familiar with. It’s a villain or villainous force that’s been hidden, and it’s implied that it has been controlling major world events all along.

Here’s what happens in the scene itself. There’s a rasping voiceover, attributed to the character “?????”, which says: “The storm, quelled. The sun, dimmed. The wolf, defanged. At last. We have balanced. Guided. Whispered. And soon, the poisoned fruit ripens. We come.”

While this is happening, slightly animated slides depicting major Dragon Age historical events flit by. They show the three elven gods in The Veilguard – Elgar’nan, Ghilan’nain and Fen’Harel (Solas) – and then the Tevinter mages who performed a blood ritual thousands of years ago to get to the Black/Golden City at the heart of the Fade. We see Loghain’s betrayal from Dragon Age: Origins at Ostagar, and we see Varric’s treacherous brother Betrand from Dragon Age 2, holding the idol of pure Lyrium, with corrupted templar Meredith and possessed magister Orsino nearby. Then we see main antagonist Corypheus from Inquisition, the Veil breach, and Morrigan’s mother Flemeth.

Shadowy hooded figures appear next to some of those characters, whispering in their ear, while other figures such as Flemeth and Corypheus are entirely replaced by them. The implication is clear: these figures influenced or orchestrated events we’ve just seen unfold.

The scene closes with black triangular symbol, which has two white lines wiggling (albeit in a slightly jagged way) across it, and it’s this symbol which provides the probable identity of the surprise new villainous force: The Executors.

The Executors are not well known in Dragon Age, but they have been referenced before. What scant information we have labels them as “those across the sea”, telling us they are beings who live somewhere other than the continent all Dragon Age games have thus far taken place in.

(Caption: Dragon Age: Origins took place in Ferelden, at the bottom; Dragon Age 2 in Kirkwall, which is a city on the Waking Sea; Dragon Age: Inquisition took place all around the Waking Sea, stretching as far West as Orlais; and Dragon Age: The Veilguard takes place in Tevinter, Nevarra, Arlathan Forest, and stretches East to Rivain. When David Gaider created the world, he purposefully contained it with mountains and seas, but now, perhaps, we’re ready to go beyond them.)

The only specific reference to Executors in Dragon Age games comes from Inquisition and a war table side quest, which has us investigate strange symbols appearing at Inquisition outposts. These symbols depict a downward-pointing triangle with two wavy lines across it – the same symbol that’s in The Veilguard post-credits scene.

If you send Inquisition advisor Cullen to look into it, he’ll uncover a message (captured nicely in this video) that reads:

“We hold your Inquisition in high esteem. Thedas’s present troubles are great, but you have the strength to meet and conquer them. More will come. We prepare for the day and hold vigil. Do not look for your men; do not mourn them. They have given themselves of their own free will to a higher cause.

“On behalf of powers across the sea,

“The Executors.”

If you send Leliana to look into it, you’ll get a message that reads:

“Compliments to your spymaster. She is a resourceful woman. Once she traced our agent to Caimen Brea, the match was ruled in her favour. Tell Sister Leliana to call off her dogs. Save them for Corypheus. We suspect, also, that she has gotten all she can from Ser Helmuth. A caterpillar on a leaf does not know there is a forest about him.

“You will hear no more from us. Our intention was to watch, and we have seen enough. Corypheus threatens us all, and the Inquisition is Thedas’s only hope for stopping him. Remember that, for the moment, we are not your enemy. As a gesture of goodwill, we share our knowledge. May it prove valuable in your coming battle.

“On behalf of powers across the sea,

“The Executors.”

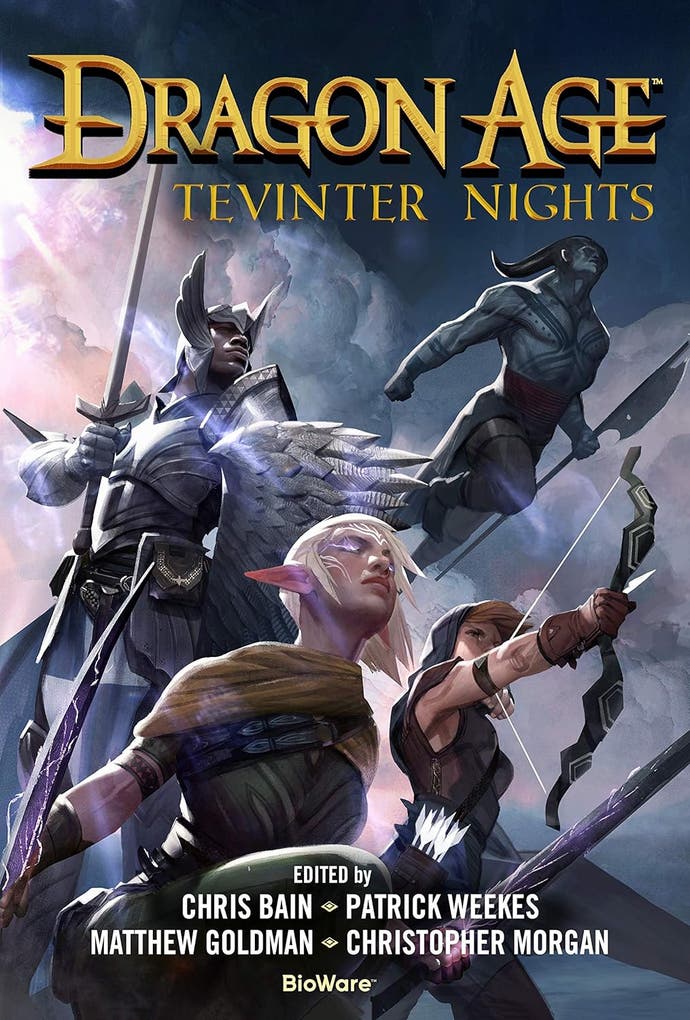

The only other specific detail about the Executors comes from a short story in the 2020 Dragon Age book called Tevinter Nights, in which an Executor features towards the end. The short story, The Dread Wolf Take You, is written by Dragon Age lead writer Patrick Weekes and it describes an Executor in a similar way to the beings we see pictured in The Veilguard post-credits scene. It reads (excerpts copied by me):

“A figure covered head to toe in dark robes of Vyrnatium samite, with a thin mesh dropping down to cover the hood. The dark robes were trimmed in a pattern Charter [a main character in the book] had never seen, twisting shapes that curled to points in places that made her eyes hurt. A cup of what looked like dark red wine sat before the figure, untouched by leather-gloved hands, but she caught a faint whiff of the ocean from his robes, and something beyond the ocean. The Executor.”

The Executor’s voice is also described as being hard to recognise or place.

“The voice that came from the Executor could have been male or female, young or old. It was less a voice than the idea of a voice, rendered acceptably but no more.”

In the book, the Executor attends a meeting in which they hope to discover the whereabouts of Solas, and an idol he possesses. The Executor also seems to be looking for a way to eliminate Solas. “We across the ocean care only for his goals and means of accomplishing them,” the Executor says.

However, Solas is also at the meeting, in disguise, and after revealing himself, petrifies the Executor, turning them to stone. Then Solas says, “I would caution you in dealing with those across the sea. They are dangerous.”

The Executors aren’t referenced directly during The Veilguard, but there are hints towards them as significant as those in the post-credits ending scene. They come during the hunt for the Mysterious Circles which you need to unlock the scene itself. Each time you pick one up, a voice interaction plays, in which you hear from a rasping-voiced character credited as “?????” – the same as in the post-credits scene.

When you pick up the first Mysterious Circle in Arlathan Forest, you hear:

“They interrupt. As predicted. As expected. As hoped.” Rook then wonders out loud what that was, to which the strange voice replies: “Learn. Adapt. Triumph.”

When you pick up the second Mysterious Circle in the Necropolis, after defeating the boss at the end of the Pinnacle of its Kind questline, you hear:

“You return. We are content.” Rook then questions why it’s here and what it wants, this voice, to which it replies: “Not now. Not yet. We will show you. Soon.”

When you pick up the third and final Mysterious Circle, at the end of the high-level Heart of Corruption quest in the Crossroads (which involves defeating one of the toughest bosses in the game), you hear:

“Fascinating. Unforeseen.” Rook then asks the mysterious voice who it is, to which it replies: “Must not reveal. Must not alarm. Soon, though. Very soon.”

Collecting each Mysterious Circle also unlocks a codex entry, written in the style of a journal belonging to an elf named Saeris, who seemingly encountered these strange beings.

I won’t relay all three entries verbatim here because they’re quite wordy. The first entry talks about finding a fragment of a circle and about it feeling “wrong” – not evil but wrong. “Being near them makes my skin crawl,” the journal says.

The second entry is more revealing. A complete circle is found in the Deep Roads and “it was strangely cold to the touch”, we’re told. “And there’s a marking. White lines and black triangles.”

The third entry I will share in full, and you’ll see why:

“I don’t know how Taeryn and I are still alive. But we shouldn’t be.

“We’d been combing through old journals, missives, anything that spoke of the air feeling greasy. That seemed to be the sign of the mysterious circles, and even the broken ones had given off some of that same quality.

“We found what we were looking for in an old scouting report from Clan Sabrae. They’d found a collapsed section of the Deep Roads that seemed to lead under the ocean – or at least they reported the smell of seawater.

“So Taeryn and I went there. We got a little deeper than the Sabrae scouts, and we found another of the circles.

“Then we saw them.

“They looked like a person, though oddly dressed. Grey robe, grey helmet, and a mask.

“Then they moved. Fast. They were suddenly in front of me. And they were reaching out – but there was something wrong with their arm. It was changing, shifting.

“I’ve fought ogres, demons, and more than one templar. But I’ve never been so afraid, or so sure I was going to die. I couldn’t move.

“Taeryn saved me. She hit it with an arrow in the chest. It stumbled back, and that broke the spell. We ran. But we could feel it behind us, and it was getting bigger.

“We lost it. I still don’t know how. But I’m not looking for these circles anymore.

“Let the past keep its secrets.”

That sounds very similar to the Executor descriptions we’ve had so far, including the smell of the ocean, and it adds the detail that they are fast and can potentially shape-shift. Gulp.

One final detail about the codex entries: when all three are aligned next to each other as cards in your codex library, they recreate the image of the symbol we see at the end of the post-credits scene. Incidentally, I can’t place what appears to be writing around the symbol. It looks like a mixture of dwarven and qunari and elven, but it’s not a match for any of them alone, suggesting it may well be something else, something new.

In The Veilguard, there’s also a mysterious wall in Dock Town, in the city of Minrathous (see the screenshots in this article for a map location), where someone has pinned pictures referencing events from previous Dragon Age games, and then attached string to them, much as an investigator would when visualising a complex case. It’s open to interpretation, but the main mystery of this scene revolves around a picture of a shadowy figure on the right-hand side; the red string connecting all previous games also connects to them. Given the implications of Veilguard’s post-credits scene, this could well be a reference to the Executors.

There’s also reference to an oversea danger at the culmination of Taash’s storyline, too, where we learn that the Qunari – who come from overseas, remember, from the north, from Par Vollen – have long battled an enemy referred to as the Devouring Storm. “If more of us flee across the ocean, it means our people failed,” the translation of a sacred tablet tells us. “Prepare then for the Devouring Storm.” Hearing this, our player character Rook responds: “You know, the more we find out, the more it seems like there are big evils of some sort everywhere.” It’s a clunker of a line, but it’s a telling set-up for something new. Does this also refer to the Executors, or something the Executors are involved in?

There’s just enough groundwork, then, to suggest BioWare seeded these Executors purposefully, years ago – though it’s so subtle that their revelation still comes as a shock. I asked David Gaider, the original creator of Dragon Age’s world and lore, about the Executors, because we talked recently about an “uber-plot” BioWare created detailing the series’ overarching storyline and I wanted to know whether these Executors were on it. But Gaider respectfully declined to comment, saying this was a question for BioWare now and not him. I asked BioWare for a comment accordingly, but EA replied saying it didn’t have anything further to add.

However you feel about the Executor surprise, they do offer Dragon Age something it desperately needs: a change. Across four games now, we’ve fought the pestilence known as the Blight, with its archdemons and darkspawn, and we’ve fought over-reaching demons from the spirit world of the Fade. And we’ve done it primarily in one place – the only continent in the known world of Thedas. Perhaps it’s finally time for BioWare to expand upon this world and for us to set sail elsewhere.

What’s more, The Veilguard has tied up a lot of the ongoing story arcs we’ve been following. We now know what the Blight is and how it was created, and how it was being controlled, and the beings who were controlling it have been destroyed. The only godlike being of elven legend who remains is Solas, and he’s locked himself away in a magical prison of his own making. The dragons referred to as Old Gods have all gone – only the Old God Baby from Origins remains, and we don’t know his whereabouts. What’s left, really, are loose ends to pursue out of curiosity; we lack an active threat to tie it altogether, which the Executors could give.

It’s intriguing; if the Executors have had a hand in all previous major world events, it would mean they’ve been around for thousands of years – long enough to influence the Tevinter mages and to be aware of the true nature of the elven gods, and events they were wrapped up in. That Solas knows of them strengthens this idea. But are they individual beings who’ve lived that long, which would make them individually very powerful, or is this an organisation that’s spanned millennia and managed to infiltrate empires and organisations at will?

If they are individually powerful (and their description in the Final Mysterious Circle codex in The Veilguard suggests they are), then what place do they hold next to entities such as Titans and godlike elves such as Solas? The way Solas petrified one so easily in the Tevinter Nights book suggests he overpowers them. So what are they, and perhaps more importantly, what do they want? What “poisoned fruit” do they refer to that has now ripened? Are we about to uncover a whole new kind of enemy somewhere we’ve never been before or have they twisted something we already know? Where do the Executors even live? There’s plenty to think about.

It’s a new mystery for a new era. I only hope that in establishing it, BioWare honours what came before rather than smothers it. Here’s to another 10 years of wondering?

Dragon Age trilogy remaster “wouldn’t be easy”, because hardly anyone at BioWare knows how its old engine works

Following a seemingly solid launch for Dragon Age: The Veilguard, there’s probably a fair few series newcomers considering delving into the original trilogy. But anyone hoping for a Mass Effect: Legendary Edition style remaster shouldn’t hold their breath; Dragon Age: The Veilguard creative director John Epler says the project “wouldn’t be easy” because hardly anyone left at BioWare knows how the studio’s old engine works. Mass Effect: Legendary Edition was well-received when it launched back in 2021, introducing the likes of improved performance and visuals, enhanced models, new lighting, gameplay tweaks, and more. It was a welcome finessing of a classic trilogy, and the kind of treatment most would probably agree BioWare’s other beloved series deserves. However, in a recent interview with Rolling Stone (thanks PC Gamer), Dragon Age: The Veilgaurd creative director John Epler – who’s been with BioWare since the original Dragon Age’s release back in 2009 – noted that while he’d love to see the trilogy get the remaster treatment, it would be a challenge due to the games’ proprietary engines. To see this content please enable targeting cookies. Manage cookie settings Here’s a video version of Eurogamer’s Dragon Age: The Veilguard reviewWatch on YouTube Unlike the Mass Effect trilogy, which was developed in Unreal Engine 3, Dragon Age Inquisition was created using EA’s Frostbite engine, while Dragon Age 1 & 2, more problematically, were built using BioWare’s own Eclipse Engine. “I think I’m one of about maybe 20 people left at BioWare who’s actually used Eclipse,” Epler explained. “[Remastering Dragon Age is] something that’s not going to be as easy Mass Effect, but we do love the original games.” But there’s perhaps some small hope for Dragon Age fans, given Epler didn’t entirely shut down the idea. “Never say never,” he added, “I guess that’s what it comes down to.” Of course, EA’s interest in giving Dragon Age the Legendary Edition treatment – and indeed its continuing interest in the series as a whole – will likely hinge on the success of Dragon Age: The Veilguard, which appeared to get off to a solid start when it launched last week. The publisher hasn’t yet trumpeted any official figures, but The Veilguard did manage an all-time peak of 89,418 concurrent players on Steam, setting a new record for a single-player EA game. What that means for The Veilguard’s future is unclear, but speaking ahead of launch, Epler said BioWare’s “full attention… has shifted entirely to the next Mass Effect”, meaning it had no DLC plans, beyond “quality-of-life improvements and a handful of smaller content updates”. Regardless of what happens next, Dragon Age: The Veilguard is a bit of a treat. “What BioWare has managed to accomplish here, in the face of all the pressure it’s faced since Dragon Age: Inquisition came out 10 years ago, is extraordinary,” Eurogamer’s Robert Purchese wrote in his five star review. “The Veilguard is exquisitely realised and full of sophistication across systems and storytelling. It’s warm and welcoming, funny and hopeful, gentle when it needs to be, and of course it’s epic – epic in a way I think will set a high bar not only for BioWare in years to come but for role-playing games in general. This is among the very best of them.”

Mario & Luigi: Brothership review – mostly clear skies

A relatively minor instalment, but in a series this magical, that’s still good news.

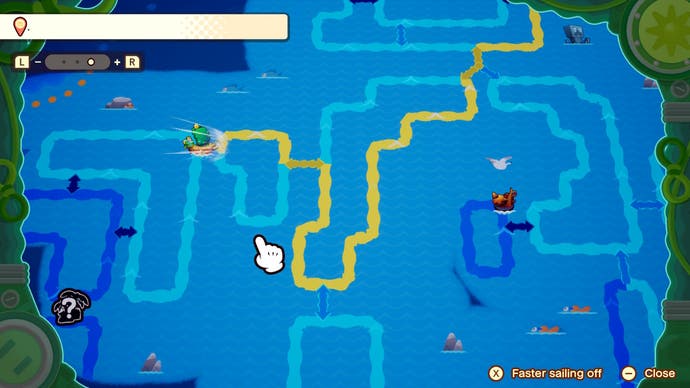

The telescope is not quite a telescope, but it still works like one. And, more importantly, it still feels like one. You put your eye to the glass and then you move left and right to scan a glorious horizon drawn in sunny skies and churning ocean currents. What’s out there? What’s waiting for me? Where next?

This is my favourite moment, my favourite little ritual, in Mario & Luigi: Brothership. Brothership’s the latest in a much loved series of RPGs in which the brother in red and the brother in green head off on an adventure together, completing quests and side-quests, engaging in exploration and puzzling, and getting stuck into turn-based battles. Brothership’s best new idea lies with the telescope, and it’s also hinted at in the game’s name. This time, you float around on a hub that’s also a ship – it’s also an island, incidentally, and it’s called Shipshape, which isn’t a bad pun – and you’re regularly tasked with tracking down the scattered islands that make up the world of Concordia, before climbing each island’s lighthouse and using it to connect the island to your home vessel. Gather those islands. Reunite the world. Onwards!

Thematically, this is all a little muddled, I know. Islands, but you connect them all via lighthouses? And almost everyone I meet is a kind of anthropomorphic plug socket or computer port? At times – any time you think too much about it – Brothership’s narrative can feel like the joke adventure that Paper Mario once sent Luigi on to explain his absence from the game. Mario would be off on a quest that made some kind of sense, but every now and then Luigi would check in with some true RPG weirdness. You know, like collecting islands, or hanging out with talking plug sockets.

None of this matters, because the ship and the ocean means that every hour or so, Brothership gets to send you somewhere new. You spot an island on the sea, you play a little game to connect your currents and head for it, you spend any travelling time levelling up or side-questing on previously explored islands that often change a little overtime, and then, when you get close: into the telescope – the telescope that is also a canon – and off through the sky to a fresh beach, a fresh world.

Sometimes, but not always, Brothership uses these islands to genuinely reinvent the game. There will be characters to meet and self-contained stories to coax to their conclusions, with puzzles that fit in thematically and set-pieces that feel truly joyous and shift the genre a little. These things happen most frequently in the back half of the game, I want to say, and I don’t think they should be spoiled. Some of the time, though, the island’s largely just a new biome – a desert, jungle, a garden – and a home for more puzzles and trinkets and combat. No matter. This stuff is still great.

The first Mario & Luigi game was more than great, of course. Superstar Saga, back in the days of the GBA, was a proper classic, and it was a classic largely because it made so much fun from the idea that you were controlling two characters rather than one. I remember precision arpeggiated jumping just to get the brothers up staircases, and sequences in which I had to control both of them as we faced off against the ultimate foe: a skipping rope. What days! By the time of Brothership, it’s all cooled off a little. Out in the world, you can make Luigi jump if you want, but a lot of the time he takes care of himself as he follows Mario around. But you can use a trigger to get him to interact with highlighted objects, and then – then there’s Luigi Logic.

Luigi Logic is the game at its most lovable, I think. Every now and then, exploring the world or facing the boss, you’ll reach a kind of impasse. Luckily, Luigi will often have a brainwave, leading to a little set-piece puzzle out in the world, or a mini-game that does massive damage to a boss. These moments are often pretty straightforward, but they’re presented beautifully. A close-up of Luigi pondering, frowning in concentration, and then it all dawns on him. The instance of the fingerpost! Luigi Logic.

These moments often lead to sequences that feel like the classic Mario & Luigi games. Luigi will man a switch while Mario moves off on platforms that Luigi is then controlling, or through a maze with pipes and junctions that Luigi can turn. The game uses picture-in-picture on occasion, which is always a weird video game gimmick that I am thoroughly here for, and it’s just a reminder that at the centre of these fairly traditional RPGs is a special ingredient: two players, a knife and a fork.

I’ve really enjoyed Brothership, but I have caveats. For one thing, and this is maybe just my patience fraying slightly as I get older and meaner, I find the stop-startiness of it increasingly awkward. I’ll be setting off to do something and then there will be a cut-scene to dismiss or a dialogue section that I can speed up but not skip. It’s not just that it tangles the flow, it’s that it doesn’t really feel like Mario, which is commonly so rare to interrupt players. That said, I don’t know if it’s the shift in developer to a team that’s less succinct, or if it’s actually any worse here than it has been before, so maybe chalk this one up to my gathering decrepitude.

The other big thing is that the combat system, while fun, is exposed over the course of a long game. It’s still good straight-forward fun, with Mario and Luigi teaming up to bonk enemies in a manner that requires interlacing button presses as each brother does their bit – you know, Mario jumps, Luigi catches him and lobs him back for another go, and then you reverse inputs when it’s Luigi’s turn. There are some ingenious enemy designs and bosses, and some of the special attacks have a nice back-and-forth complexity to them as you knock a shell to and fro, say.

There’s a new plug system in combat, too, which sees you unlocking special moves and modifiers that you can swap in and out, searching for synergies and managing cooldowns. But when you’re largely opting to stomp or hammer or pull off a gimmick attack, it can become just a little bit of a chore over time. I never minded battling, but I noticed several times that its puzzle sections – which had relatively few enemies to deal with – held my attention much more. Not just that, it felt like the game was following the grain of its own materials at this point. Brothership offers some lovely sequences, but the mainly-decent combat can feel like a little too regular of an intrusion.

Yes, yes. All of this stuff is a little annoying. But while Brothership isn’t the series at its very best, it’s still a Mario & Luigi RPG, and these always contain moments of colour and wit and invention that I’m extremely glad I was present for. Mario and Luigi are already money in the bank, in other words. Throw in a bit of island hopping and I’m still happy.

A copy of Mario & Luigi: Brothership was provided for review by Nintendo.

BioWare knew the deepest secrets of Dragon Age lore 20 years ago, and locked it away in an uber-plot doc

As I write about the secrets hidden in Dragon Age’s mysterious Fade, and as I uncover some of them playing Dragon Age: The Veilguard, one question keeps rising up in my mind.

How much did BioWare know about future events when first developing the series more than 20 years ago? That’s a long time, and back then BioWare didn’t know there would be a second game, which is why Dragon Age: Origins has an elaborate and far-reaching epilogue. Why lay so much lore-track ahead of yourself if you don’t think you’ll ever get there?

But look more closely at Origins and there are big clues suggesting BioWare did know about future Dragon Age events. There are obvious signs in the original game, such as establishing recurring themes like Old Gods and the Blight and Archdemons. But there’s also Flemeth, Morrigan’s witchy mother, who’s intimately linked to events in the series now – more specifically: intimately linked to Solas. Does her existence mean Solas was known about back then too?

There’s only one person I can think of to answer this and it’s David Gaider, the original creator of Dragon Age’s world and lore. We’ve talked before, once in a podcast and once for a piece on the magic of fantasy maps, where we discussed the creation of Dragon Age’s world. And much to my surprise, when I ask him what he and the BioWare team knew back then, he says they knew it all.

“By the time we released Dragon Age: Origins, we were basically sure that it was one and done, but there was, back when we made the world, an overarching plan,” he says. “The way I created the world was to seed plots in various parts of the world that could be part of a game, a single game, and then there was the overall uber-plot, which I didn’t know for certain that we would ever get to but I had an understanding of how it all worked together.

“A lot of that was in my head until we were starting Inquisition and the writers got a little bit impatient with my memory or lack thereof, so they pinned me down and dragged the uber-plot out of me. I’d talked about it, I’d hinted at it, but never really spelled out how it all connected, so they dragged it out of me, we put it into a master lore doc, the secret lore, which we had to hide from most of the team.”

This uber-plot document was only viewable on a need-to-know basis, he says, and only around 20 people on the team had access to it – other senior writers mostly. And even though Gaider left the Dragon Age team after Inquisition, and then eight years ago BioWare altogether, meaning he didn’t work on The Veilguard at all, he believes – by looking at the events in the new game – his uber-plot lore “has more or less held up”. That’s impressive.

What’s even more impressive, or exciting, is that back then he also envisaged a potential end state for the entire Dragon Age series – a point at which it would make no sense for the series to carry on. “I always had this dream of where it would all end, the very last plot,” he says, “which I won’t say because who knows, we could still end up there. But the idea that this uber-plot was this sort of biggest, finite… That the final thing you could do in this world that would break it was there as a ‘maybe we would get to do that one day’… There was just the idea of certain big, world-shaking things that were seeded in that arc, some of which have already come to pass, like the return of Fen’Harel.”

You’ve read that correctly: the idea to have Fen’Harel, also known as the Dread Wolf, reappear, was seeded all the way back then, way before Inquisition – the game in which he does actually reappear. But the concept for Solas, as a character who was Fen’Harel in disguise, was a newer idea. “That spawned from a conversation I had with Patrick [Weekes] and a number of other writers,” Gaider says, “as an idea of ‘what if you had a villain that spent an entire game where he’s actually in the party and you get to know him?’ Now, the god version and his larger role in the plot, yes that was known, but not that he would be presented as a character named Solas.”

Fen’Harel being known about means the other elven gods were known about, which means all of that stuff Solas reveals about his godly siblings – that they’re not gods at all but evil elven mages he locked away behind the Veil – was known about back then too. “Oh yeah,” Gaider says. “Everything that Solas tells you [at the end of Inquisition DLC, Trespasser]: it’s all part of that original uber-lore – that was all in our mind.”

But why have so much lore if you’re not certain you’ll get to ever realise it? Well, to create a believable illusion. By creating an “excess” of lore, as Gaider describes it, Origins made Thedas feel like an old and believable place. A place with history, rather than a Western set that was all facade and no substance.

BioWare also did something canny with the lore it did relay then, too: it shared it through the voices of characters living in the world, making it inherently fallible. In doing this, Dragon Age veiled its truths behind biases. The church-like organisation of the Chantry proclaims one truth, while the elves and dwarves proclaim another. Sidenote: you can experience this yourself through different racial origin stories in Dragon Age: Origins. This way, there’s no one, objective, irrefutable, truth.

“To get the truth, you kind of have to pick between the lines,” Gaider says. So even though elven legends are coming true through the existence of Solas and The Veilguard’s antagonist gods, it doesn’t mean that’s the one and only truth. There’s truth in what the Chantry teaches and what the dwarves say, he tells me, which ignites my curiosity intensely.

BioWare has also been tricksy in how it’s rubbed out the lore the further back in time you go. “In general, the further the history goes back, we always would purposefully obfuscate it more and more,” Gaider says – “make it more biased and more untrue no matter who was talking, just so that the absolute truth was rarely knowable. I like that idea from a world standpoint, that the player always has to wonder and bring their own beliefs to it.”

It leads into a founding principle of Dragon Age, which is doubt – because without it, you can’t have faith, a particularly important concept in the series. It’s where the whole idea of the Chantry’s Maker comes from and with it, the legend about the fabled Golden City – now the Black City – at the heart of the Fade. This is the very centre of the lore web, and, I imagine, it’s close to the series endpoint Gaider imagined long ago. All secrets end there.

Did Gaider know what was in the Black City when he laid down Origins’ lore? That’s the question – and it startles me how casually he answers this. “Oh, yeah,” he says. “What was in the Black City: that’s the uber-plot. I knew exactly.

“Was it as detailed in the first draft of the world?” he goes on. “No. I had an idea of the early history because that’s where I started making the world. So the things that were true early-early: I knew exactly what the Black City was and the idea of what the elves believed, and what humans believed vis-a-vis the Chantry – that was all settled on really early. Then I expanded the world and the uber-plot bubbled out of that.”

Gaider shows me the original cosmology design document for Dragon Age: Origins as if to prove this – or rather for the game that would become DAO. The world was known as Peldea back then. I can’t share this with you because I see it via a shared screen on a video call, and because Gaider doesn’t want me to, mostly because the ideas are so old they’re almost unrecognisable from what’s in the series now. But I can tell you it’s a document that’s just over a page in length, and that there’s a circular diagram at the top showing the world in the middle and the spirit realm ringed around it. And on that document is reference to the Chantry’s beliefs about a God located in a citadel that can be found there.

The Fade wasn’t known as the Fade back then, either, but as the Dreaming, because it’s the place people go when they dream – an idea that lives on still. And if that sounds familiar to any fans of The Sandman among you, it should. “I’d say The Sandman series was probably fairly prominently in my head,” says Gaider. “I liked that amorphous geography that was born from the psyche of collective humanity. I’d say yes, if I was to point at something specifically, that’s probably where the very first inspiration of it took root.”

It’s a lot to take in, but it reinforces the admiration I have for Dragon Age. Just as I have when hearing about the creation of my other favourite fantasy worlds, such as A Song of Ice and Fire, I begin to understand the magnitude – and the deliberateness – of the plotting that went on.

I wonder if one day the Dragon Age series will end in the way Gaider first imagined, albeit slightly altered by the many other pairs of hands shepherding it along now. What a curious feeling it must be to know, so many years in advance, where things might go.

Where that end is, I don’t know, but I do know we’ll take a significant step towards it in The Veilguard. After all, we’re coming into contact with gods who were there at the recorded beginning of it all. “Yeah – we have access to people who can tell us the truth from first-hand experience,” Gaider says, “although again, it depends on what the writers did with it. But if they continued the tradition of Dragon Age, you never know for sure if Solas is telling you everything, or what you’re learning is the entire truth.

“But yes, some of the big mysteries are being solved. I mean, will they one day definitively tell you about the Maker? Will we crack the big mysteries of the world and just make them answered finally? And does that ruin one of the central precepts that Dragon Age is founded upon? Maybe,” he says.

“Ultimately, that lore, when you make it big and you hint at it and hint at it and hint at it, it becomes a Chekhov’s Gun of sorts. Eventually you got to pony up.”