With the season of giving now officially upon us, Jingle Jam has unveiled its latest PC charity bundle – this year featuring the stellar likes of Citizen Sleeper, Shadows of Doubt, and Frostpunk, which can all be snapped up in support of a bunch of good causes. In total, the Jingle Jam 2024 Games Collection feature 18 titles (all supplied as Steam codes), and there’s a lot of good stuff to be found. For the most part we’re in the realm of indies, although Sega and Two Point Studios’ enormously enjoyable Two Point Campus sneaks in too. Also up for grabs are ColePowered Games’ wildly ambitious procedurally generated detective noir Shadows of Doubt (which we gave three stars back in October), superb sci-fi narrative adventure Citizen Sleeper (Recommended), survival city builder Frostpunk (also Recommended), and minimalist puzzler Patrick’s Parabox (four stars!). The Jingle Jam 2024 Games Collection official trailer.Watch on YouTube But there’s more: roguelike card battler Widlfrost is in there (this one made Bertie’s Games of 2023 list), as is wonderfully engaging sci-fi construction sim Mars First Logistics, sticker store management game Sticky Business, crustacean-themed Souls-like Another Crab’s Treasure, and the sequel to acclaimed 2018 tabletop-style RPG adventure, For the King 2. Also included is the well-received blackjack roguelike adventure Dungeons & Degenerate Gamblers, Geiger-esque horror Scorn, action-tower defense game Orcs Must Die 3, dystopian racer Death Sprint 66, dating sim action-RPG Eternights, card-battling rogue-like Hadean Tactics, hand-drawn puzzle adventure Submachine: Legacy, and Fight in Tight Spaces – a “stylish blend of deck-building, turn-based tactics, and thrilling animated fight sequences in classic action-movie settings”. And if you prefer you lists in bullet point form: Dungeons & Degenerate Gamblers Wildfrost Two Point Camps Shadows of Doubt Patrick’s Parabox For the King 2 Citizen Sleeper Another Crab’s Treasure Mars First Logistics Sticky Business Hadean Tactics Submachine: Legacy Scorn Orcs Must Die! 3 Fights in Tight Spaces Death Sprint 66 Eternights Frostpunk The Jingle Jam 2024 Games Collection is a bit of corker, then, and if you’re sufficiently swayed, all the above can be acquired for a very reasonable donation of £35. Or rather, for a minimum donation of £35 – with more appreciated if you’re able, seeing as organisers are hoping to raise as much money as possible for this year’s eight selected charities. More specifically, money accrued though Jingle Jam 2024’s charity bundle will go to Autistica, Campaign Against Living Miserably, Cool Earth, Sarcoma UK, The Trevor Project, Wallace & Gromit’s Grand Appeal, Whale and Dolphin Conservation, and War Child. You can read more about each charity – and purchase this year’s games bundle – over on the Jingle Jam website. At the time of writing, it’s successfully raised £1,277,979.

Category: Management

Auto Added by WPeMatico

Threshold review – a horrifying act of corporate plate-spinning that will take your breath away

Short but powerfully unsettling, Threshold takes aim at the strange and horrifying helplessness of being a small cog in a giant corporate machine, and nails its execution brilliantly.

Threshold is the kind of horror game that keeps just enough at arm’s length to really set your mind ablaze while you’re playing. After landing a coveted job with the government, the game begins as you prepare to take on your first shift looking after an important maintenance post just outside the city walls. But before you even arrive, it’s clear that something’s a bit off. A low, angry and muffled voice directs you into a lift. There’s an oxygen meter to your left, and as you start the long ascent up to the surface you watch your supply dwindle away to almost nothing. The air is thin up here, so much so that the clerk you’re relieving, a no-nonsense chap called Mo, speaks to you via hastily written notes, as talking simply involves too much effort.

Before you can wonder ‘what the heck have I walked into?’, Mo hands you a whistle and brings you to a large horn at the centre of your work area. Blowing the whistle here makes sure the large, ominous train trundling along on the other side of the river keeps moving at the ‘expected pace’, and you’ll need to rush back here every time it starts to slow down to make sure it keeps up to speed. For what purpose, you’re not told. Only that this is what the capital dictates. Trouble is, with the air being so scarce up here, blowing that whistle is surprisingly taxing, so you’ll need to clamp your teeth down on tiny little Air Cans to get your breath back every time you start wheezing or black, pixely veins start clouding your vision. And the more Air Cans you consume, the more bloodied the little picture of your mouth starts to become in the top left corner of the screen.

But this strange and unnerving setup is just the tip of the iceberg. As you settle into a gentle rhythm of keeping the train going and fetching tickets from a special machine to swap for more air cans, questions about the reality of this place start building up – both for your clerk and you as a player. Why is the toilet locked? And why does the river drain when the train slows down? Who was Ni, the clerk you’ve replaced? And why does Mo hate them so much?

Your clerk will log some of these questions in their own mind, but finding answers to them are harder to come by. Threshold does a brilliant job of letting these thoughts sit with you for a while, seeding its ideas upfront and without context so they swill around in your head, before eventually proffering up answers of its own – though whether you believe them is another matter entirely. The sparse and potentially unreliable script repeatedly butts heads with the clear evidence in front of you – though the shifting textures of the game’s PS1-era visuals certainly contribute to everything feeling just a little bit otherworldly at the same time. Still, even when answers do come, they’ll sometimes just beget even more questions in the process, and Threshold’s greatest strength is how it gives you the space to form your own conclusions about what’s really going on here.

All the while, of course, you’ll still need to keep that train running. As the cycle of corporate plate spinning begins anew, other tasks from Mo start creeping in to split your attention, such as collecting stray planks of wood or keeping the end of the river clear of ‘unwanted biomass’. But all of them are designed to needle away at that one fundamental mystery, introducing ever stranger elements to fire up your imagination. The more you engage in the job, the more inane it starts to appear, and it becomes a highly effective tool to fuel your desire to find out the truth of this place once and for all.

On a moment-to-moment basis, the gradual pile-up of tasks is also just a satisfying exercise in its own right. The water filter where the biomass collects is quite a walk away from the horn and the machine that dispenses your air can ticket, for example, and wading through the water is even more of a strain on your already fragile lungs. The time and oxygen it requires all needs to be weighed up against the pace of that infernal train, and every time I contemplated going down there, I found myself straining my ears for that tell-tale screech of the train’s brakes that always precedes when it’s about to slow down. You’ll wonder whether there’s something better you could be doing with your time, another task you could complete along the way, or when would be best to bite down on yet another air can so you can make the most of your remaining breaths. Even as you question your role here, it’s hard to resist becoming the perfect picture of industrial efficiency.

Indeed, there’s never so much on your plate that you can’t keep things ticking along quite nicely, despite the ever-present threats to your overall wellbeing. If the train starts lagging behind, for example, your air can dispenser stops working, and it won’t start back up again until the expected pace has been met again. You’ll therefore need to keep a healthy supply of air cans and tickets with you at all times, just to make sure you’re not caught short. But as long as the train keeps running, the ticket machine will keep punching out cards for you – which it does so with a very pleasing chnk-chnk-chnk that only gets faster as the train’s expected pace increases. It would be hard to do a bad job or completely run out of air, in that sense, but the ease with which you’re able to course-correct doesn’t make the busy-work any less compelling in the moment.

That’s partly because Threshold is never quite content to let that general status quo last for very long. Rather, it’s the gradual and expertly paced disruptions to your working rhythm that make the game feel so thrilling and alive, like there’s some kind of unknowable force wriggling beneath the surface just out of sight. As the earth begins to shake, the river starts to swell and the mountain shifts ever more violently beneath your feet, the fabric of the world itself reflects that growing pressure cooker you’ve got bubbling up in your own mind, everything building and building until the centre can no longer hold and it all erupts in one of the most spectacular endings I think I’ve seen all year.

And yet, even after all that, Threshold still isn’t quite ready to relinquish its grip on you, as a closing teaser reveals yet another layer of the game’s underlying truth. It’s just enough to pull you back in for another shift, and to keep seeking answers to its impossible questions. There’s a sense you’ll never quite get your arms around the full extent of the role your clerk’s been given, but it’s the act of reaching for it that makes Threshold so deeply and utterly mesmerising.

A copy of Threshold was provided for review by publisher Critical Reflex.

Planet Coaster 2 review – buckled potential

Planet Coaster 2’s flexible creation tools are as compulsive as ever, but the fun butts up against an exhausting UI, uninspired management gameplay, and conspicuous content gaps that feel like cynical spaces for DLC.

I bloody love a theme park: the sights, the smells, the gleeful screams, the sense of utter transportation. But most of all, I love the breathless clash of science and art behind these thoroughly encompassing illusions. I’m the kind of theme park nerd who still gets genuinely giddy when they see technology and creativity crash together like this, and who’s been daydreaming their perfect rides and coasters into existence since a run-in with Disney’s Haunted Mansion at the age of three became a bit of an obsession. For people like me, the original Planet Coaster was a dream. For all its flaws, it was a brilliantly implemented, beautifully presented suite of creative tools capable of turning theme park flights of fancy into digital reality, and its sequel promises the same, but more.

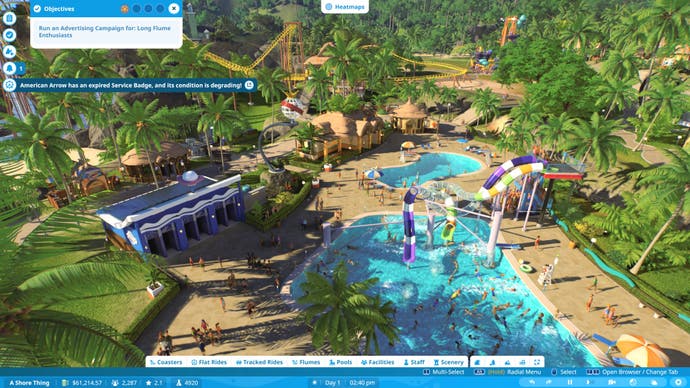

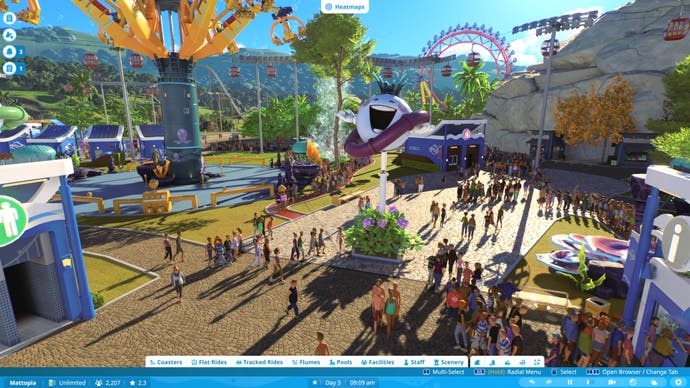

Like its predecessor, Planet Coaster 2 is an immediate head turner; a glorious fusion of art, animation, sound, and music that brings those creative whims to wonderfully convincing life – a world of whirling metal, blinking lights, and the delighted screams of guests, to be experienced on high or at ground level. Strip away the presentational pizzazz, of course, and Planet Coaster 2 remains indebted to Chris Sawyer’s seminal RollerCoaster Tycoon, barely straying from the template established over a quarter of a century ago. It’s a game built around the intricacies of park management; of hiring staff, constructing rides, and providing key amenities – all to please guests and make enough profit that the operational loop can continue indefinitely. But once again, Planet Coaster 2’s real strengths lie in the depth, breadth, and flexibility of its design and customisation tools.

This is a sequel of gentle evolution rather than sweeping reinvention, which isn’t to say its refinements aren’t immediately apparent – Frontier has clearly listened to feedback from Planet Coaster 1, even if it feels like its most notable improvements are specifically catered toward the YouTube content creator contingent with days to spend fashioning their marvels of intricate design. Its new lighting engine, for instance, isn’t just pretty, it’s practical; enclosed spaces are actually dark, meaning proper dark rides are finally possible without clunky workarounds.

Then there’s the optimisation. Unlike its notoriously spluttery predecessor, Planet Coaster 2 is far more capable of keeping up with players’ creative whims without immediately turning into a slideshow. Track ride construction generally feels less fiddly; flat rides can now be stripped back and fully themed with décor pieces – invaluable for those wanting a more cohesive aesthetic flow across their parks – while seemingly minor additions such as object-scaling and scenery brushes are major game changers. Elsewhere, pools and flumes have been introduced, satisfying the endless clamour for water parks among the community.

Planet Coaster 2’s various play modes are more clearly defined now, too. There’s a campaign mode, for instance, that goes to some entertainingly weird places as it cheerfully turns the fundamentals of park building into objective-based challenges. That said, its tendency to prioritise dad-tier jokes over helpful explanations – and the frequency with which any attempts at creativity butt up against arbitrary limitations – make it a bit of a drag. There’s also a Franchise mode, enabling players to work together, clan-like, in a globe-spanning grasp to top the leaderboards by satisfying weekly challenges, and there’s support for asynchronous co-operative building, too. Finally, for those simply wanting to maximise their creative freedom, there’s a highly customisable sandbox mode, enabling players to shift the balance between park management and design as they say fit.

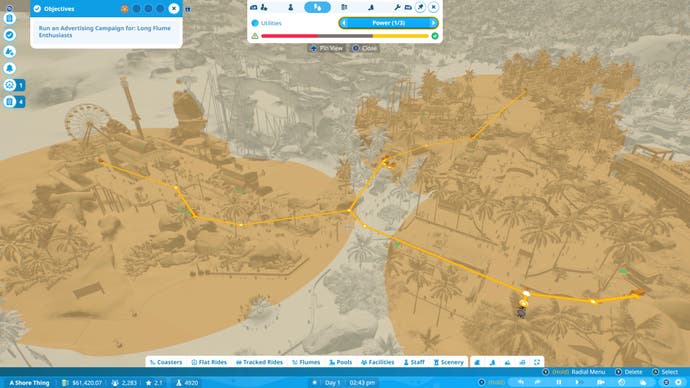

What Planet Coaster 2 lacks, though, is any meaningful strategic evolution or sophistication. It jettisons some of its predecessor’s mechanical breadth too, with the likes of restaurants, hotels, and security all now inexplicably removed. The original Planet Coaster was, of course, a desperately uneven affair, its powerful creation tools massively overshadowing an anaemic management core, and it’s disappointing – if perhaps not especially surprising – to see those weaknesses carry over to the sequel. It might feature a checklist of new management options – from water filtration to power distribution – but the implementation is uniformly superficial. Even water parks, Planet Coaster 2’s flagship new feature, just sort of exist – a couple more holes to dig, staff to employ, and rides to build – with little in the way of extended integration.

For all its building refinements, Planet Coaster 2 feels like it marginalises its management side even further, its two halves co-existing, occasionally intertwining, but never in particularly interesting or convincing ways. It’s a backward step compared to Frontier’s wonderful Planet Zoo, which struck a compelling balance between park management and beautification. And it’s especially weak in comparison to Texel Raptor’s Parkitect, created with a fraction of Frontier’s resources, which despite ostensibly being a retro throwback, felt like a genuine evolution of the classic theme park sim formula. Parkitect’s canny logistical layer of goods distribution, meaningful distinctions between ‘backstage’ and ‘front of house’, not to mention its impactful weather system, all brought a genuine sense of strategic cohesion between its two halves. By comparison, the handful of elements that Planet Coaster 2 does borrow from Parkitect – weather and scenery scoring – feel dramatically underdeveloped and awkwardly siloed.

Even more so than the original, Planet Coaster 2 feels like a game for the builders and tinkerers, the look-what-I-made content creators, and that’s perfectly fine, even if it does feel like a missed opportunity. Frontier’s sequel has the same unquestionable kind of hypnotic allure as its predecessor when it comes to building and design – arguably even more so, given its multitude of toolkit refinements – hours vanishing in a happy haze of meticulous rock placement, or in getting the banking sweep of your brand-new coaster just so. The trouble is, for all it gets right, Planet Coaster 2 often feels strangely retrograde – cumbersome, counterintuitive, or just plain contradictory – with an infuriating knack of getting in its own way.

Simply navigating menus is often an exercise in fiddly frustration, with Frontier’s attempt to design an interface that works for both keyboard and mouse and controllers never quite working for anyone. Menus are unintuitively organised, key information is often missing or obscured through poor or inconsistent presentation, advanced settings frequently remain unexplained… On it goes in a similar slapdash fashion. Why, for instance, does the Workshop not have a filter for flat rides, of all things? Individually, these feel like surmountable quirks, but all together they’re just draining.

It doesn’t help either that feedback is often so poor, even contradictory, that it’s hard to tell what’s a failure on your part or a failure of the game. “Staff are trying to access a staff building which is at full capacity”, I am informed at one point, quickly followed by the message, “There is no staff building”. Encouragingly, Frontier has already started to address some of Planet Coaster 2’s more egregious issues, with more substantial tweaks coming in December, but it’s still hard to shake the sense of backward slides elsewhere.

Sure, the ride selection is genuinely great, with some wonderful titillating flourishes – tilting coaster platforms, backward flumes, oh my! But as easy and enjoyable as it is to build the ‘park’ bit of your theme park, Planet Coaster 2 seems to flounder on theme. Gone are the visually distinct archetype themes seen in the original game – pirate, sci-fi, spooky, and western. Instead, replaced by far less distinct options: aquatic, mythology, Viking, tropical resort, and cheerily corporate. It’s a mix that results in a sort of bland sludge of vaguely vacation-themed visuals – part holiday resort, part generic amusement park – that don’t exactly sizzle with creative potential. Furthermore, Planet Coaster 2’s building blocks leave a lot to be desired, pre-built decorations, animatronics, and in-house scenery blueprints all in decidedly short supply.

After a few hours in the original Planet Coaster, I’d built a surprisingly elaborate Pirates of the Caribbean knock-off, complete with sword waving buccaneers, burning ships, and cannon balls splashing in the water; by comparison, the most exotic corner of my park in Planet Coaster 2 is a sad cave with a singing eel. Yes, it’s absolutely possible to improvise something more fantastical using geometric shapes and fiddly little props, but not everyone will want to go so deep into the tools. Of course, Planet Coaster 2’s new in-game Workshop means design-minded players can upload and share their creations with anyone hoping for a more casual play experience – but it all feels a little distasteful, as if Frontier’s offloading key foundational work onto the community. And Planet Coaster 2’s more conspicuous gaps feel even more cynical when they’re accompanied by £18 launch day DLC.

At its best, Planet Coaster 2 captures much of the magic of its predecessor, where immaculate presentation and powerful tools manifest a game of endless creative potential. But its undoubted pleasures are haunted by interruptions and frustrations, missed opportunities, and just far too many conspicuous holes where it feels like something vital should be. There’s a chance things will improve as Planet Coaster 2 evolves, but right now, for all its core refinements, it often feels lesser than its predecessor in too many ways.

A copy of Planet Coaster 2 was provided for review by Frontier Developments.

I tried Ruben Amorim’s tactics with Manchester United in Football Manager, and the results were all over the place

I unironically think I’m pretty good at Football Manager. By this point, I really better be – I’ve been playing this game for anywhere between 200 and 400 hours a year, every year, since I caught the bug sometime around 2008. But then in each of those years I do always play as Manchester United, the team I support, and unlike the United of the real world, it’s easy enough to see things regularly going well with a bit of clever spending and tactical nous – in my last save, I just won the quadruple with United, alongside a full “invincibles” season in the Premier League.

If that all sounds like a bit of typical United fan bragging, however, worry not! A severe humbling follows.

After more or less ‘fixing’ the club – the task I set myself with each new game, and in doing so clearing all of the main challenges of my most recent save – I’ve been looking for a bit of a new spin to fill the void while we wait for FM25. Lo and behold, here’s real-world Manchester United finally agreeing to bring in a new manager, the widely admired 39-year-old Ruben Amorim of Sporting CP. The perfect new challenge has arrived. And so, in light of the excessive interest in how his teams play – and a wonderful 4-1 spanking of Man City in the Champions League earlier this week that deserves its own celebration – I thought I’d see how Amorim’s already famous 3-4-3 translates to United in the world of Football Manager.

Part 1: Figuring out how Amorim plays

If you’ve been broadly plugged into the football world over the last week or so you’ll be fully aware that Ruben Amorim really likes to play 3-4-3. In fact, he’s only played with a standard back four – the default for the English Premier League – in his very first three games as a manager several years ago, before ditching it forever.

Unfortunately, that’s where my real certainty about Ruben Amorim ends. And in Football Manager, we have to go a lot deeper than just mere formations to get things moving. Where things get much harder is in interpreting how exactly that 3-4-3 works in practice.

First up, the research. I am shamelessly obsessed with football tactics, and so am happy to admit I’ve a few regular go-tos for full tactics nerd breakdowns, which are naturally where I started here.

One is a Manchester United podcast called Devils In The Details, run by Aaron Moniz and Kees Hemmen – a pair of young, yet also enjoyably world-weary data analysts who support the club. Another is the handful of Twitter ‘tacticos’ that regularly cover United: a well-known blogger who just goes by Harrison (or @htomufc); and Varun Vasudevan, who runs another account and personal blog called The Devil’s DNA. There’s also Third Man Runs, another excellent, non-Manchester-United-specific tactical blog that wrote a three-part series on Amorim’s ‘game model’ with Sporting in April earlier this year. And lastly there’s The Athletic, which has frankly rinsed the news of Amorim’s arrival with a tidal wave of articles from United experts such as Carl Anka, analytics gurus such as Ahmed Walid, and tactical historians including Michael Cox on how he plays and whether it’ll work in the Premier League. (Short answer: maybe – but we’re not here for short answers!)

Here’s the issue: as you might have guessed, everyone has a slightly different idea of how Amorim’s teams tend to play. Some describe his ‘build-up phase’, where teams move into a specific shape during situations like goal kicks to help them get past the opposition team’s own structure, as a kind of 4-2-2-2. Sporting’s wing backs drop back, the central centre-back of the three pushes up into midfield, one of the two central midfielders pushes up, one of the two players behind the striker pushes up again (fellow tactics nerds would recognise this as forming what’s called a ‘box midfield’ to overload opponents who typically only have up to three players defending the middle – this one’s actually a kind of double-box, but let’s not sweat that just yet). Others describe a 3-4-2-1, where the back three and two midfielders stay closer to their original positions. Out of possession, it’s the same: most describe an intense high-press, potentially leaving risky gaps in midfield.

But actually watching Sporting myself only makes things more complicated: against City earlier this week, Sporting played on the break, sitting into more of a back five shielded by three densely packing the midfield, one in front of them, and a lone striker, more like a 5-3-1-1. After the match, Amorim even came out and said United “can’t play as defensively” as his Sporting side has once he takes over.

As for how this works for Football Manager? My main takeaway at the moment is that this is going to be a headache.

Part 2: The setup

It’s time to settle on a plan. What’s clear – and what many of these genuinely brilliant tactical analysts agree on – is that Amorim is actually highly adaptable from one game to the next, despite being rigid in his overall reliance on a 3-4-3. Sometimes his teams focus on short passes through the middle of the pitch to get the ball forwards, using that box-shaped overload of central midfielders to bait the opposition into pressing, a bit like Roberto De Zerbi’s Brighton last season. Other times, they use quick interplay down the flanks, relying on the wing backs heavily. Others they actually go quite direct, over or around the opposition’s defensive line to their hugely prolific, channel-running Swedish forward Viktor Gyökeres.

Translating that adaptive style to FM is going to be a challenge. Football Manager is excellent at recreating a specific tactical approach, but it struggles, perhaps naturally, when it comes to one based on in-game contingencies, or that automatically adapts to your opponents. Navigating that turns out to be the biggest challenge of all.

To start off, I set things up with the quickest possible method of diving into a close-to-realistic part of United’s season. In lieu of a sparkly new FM25 database from official scouts, I download a community mod from a pair called TheNotoriousPr0 and FMTU, which gets FM24’s database as close as possible to the starting point of the current season. Despite us technically starting in 2023 here, we at least have all of summer 2024’s transfers and a few attribute updates for the youngsters.

I opt to jump into the save with pre-season partially underway to save some time, but still give me a few weeks to give the players some tactical familiarity. I turn opening window transfers off, skip my usual backroom staff overhaul, ignore my scouts’ many (justifiable) reports on where the squad can improve, and skip the opening press conference. I’ve never done this before, and it turns out this makes a lot of digital journalists default to thinking I’m some kind of arrogant chancer, but otherwise does nothing of consequence here – thankfully I won’t be around long enough for the inevitable ‘sack the manager’ campaign. My goal is to get the squad semi-familiar with the tactics, play a few games, and see how we get on.

On to the tactics, at last!

We’ve talked about overall shape, but now it’s time to get really granular. I start with a basis of the Vertical Tiki-Taka preset, which feels like the most ‘Amorim’ option, emphasising fairly short but forward-thinking passing through the centre of the pitch. (The wing back interplay, I tell myself, is something players will naturally end up using because the wing backs are likely to regularly find themselves open. I’m sort of half-right, but more on that later.)

There are a few bits of tinkering to sort though: we go for whipped crosses to work with Hojlund’s pace and physicality against unsettled defences; I stick to underlaps rather than overlaps to try and get the two attacking midfielders of that front three running beyond the ball into the box; I choose to ‘trap outside’ with the press, as typically Amorim’s sides like to funnel opponent attacks down the flanks and press them there with the numerical advantage; and I choose ‘be more expressive’ to give players freedom to problem-solve, in the hope of emulating some adaptability.

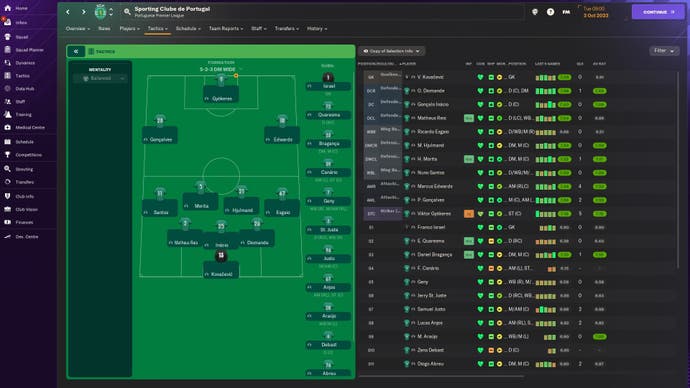

Now for the personnel. Most visualisations of Amorim’s tactics set the team up with three centre backs; two wing backs ahead of them – making it a back three by default rather than back five – then two central midfielders; two central attacking midfielders, or ’10s’; and one centre forward.

Immediately we have issues. Rasmus Hojlund is an almost perfect match for Gyökeres, with an Advanced Forward role here, Onana is great for the Sweeper Keeper role, Bruno Fernandes is obviously one of the 10s and Ugarte, who played under Amorim at Sporting previously, naturally is one of the midfielders. Everywhere else is a question mark, but let’s run through the decisions quickly.

Astonishingly, Luke Shaw is actually fit for my first pre-season game, though Malacia is out for months longer than I have to spend here. So as the only fit left-sided defender, Shaw goes in at left wing back and Mazraoui, slightly more technically proficient than Dalot, goes on the right. I am worried about depth here. (Spoiler: I am right to worry.)

In defence, the options most experts have suggested are the left-footed, progressive ball-player Lisandro Martinez at left centre back, the hulking De Ligt in the middle, and the young Leny Yoro, adept beyond his years at covering wide spaces, on the right of the three. So that’s what I start with here.

This is also where I decide to get a bit fancy. The idea of a centre-back forming part of the midfield ‘pivot’ is fun to me, and I’ve seen some analysis that Amorim occasionally has his left centre-back, Gonçalo Inácio, do that rather than the usual central one, which is rather unorthodox on top of an already very on-trend move. Inácio is a very similar player to Martinez – weaker at defending channels; excellent on the ball – and Amorim does this to protect him from that channel defending while getting the most out of his on-ball ability. So, galaxy brain moment, let’s have Martinez invert from the left, using the Libero role, just like Inácio.

In midfield, the clear best choice for a real-world partnership is energetic destroyer Ugarte alongside the more forward-thinking wonderkid Kobbie Mainoo, which makes sense to me. Eriksen is a better, more creative passer but too old and flimsy to rely on frequently; Casemiro has similar issues with creaking legs, but is a nice rotation option for Ugarte; Mason Mount I judge to be an attacking midfielder for now, as he is in the real world. And that’s really all your options.

Ahead of them is where it gets really interesting: Fernandes goes in one spot, and Hojlund’s up top, leaving the left sided attacking midfield position. So who out of Marcus Rashford, Alejandro Garnacho, Mason Mount, Christian Eriksen, Antony, Amad, and Joshua Zirkzee takes the other place in attacking midfield?

Aiming to stick with what most analysts expect the real Amorim to do, I go with Marcus Rashford. He’s very loosely familiar with the position, according to FM, and so I get him retraining as a Shadow Striker pronto, and attempt to set him up here as a runner from deep who often joins Hojlund on the last line of the opposition defence as part of the 4-2-2-2 in possession. As it turns out, this is one of many, many mistakes I made with this starting line-up.

Part 3: The experiment begins with a wobble

Five minutes into our first friendly against SK Rapid (a team I have, with apologies, genuinely never heard of), we are 1-0 down. We go on to lose 3-2, only mustering about 0.43 expected goals (xG) to their 1.56. In other words, they had better chances and finished them well, while we did very well to even score twice. Hojlund looks dangerous and Fernandes got a goal and an assist, which is good! Everything else looks very bad.

What else is very bad? Luke Shaw is injured, about 35 minutes into the first friendly of pre-season. With backup Tyrell Malacia still 3-4 months away from recovering from the same long-term issue that plagues him in real life, we’re now without a recognised left wing back in the squad. Time for plan B, something a few pundits have mooted as an option since both Shaw and Malacia are injured here in the real world too: Garnacho at left wing back.

The issue here is, according to FM24, Garnacho cannot play left wing back. He has such little familiarity with the role that if you put him there, because of the way FM positions work, the star rating that indicates his general effectiveness drops to an unusable 0.5 out of five. So, time for what is effectively plan C already: we change the formation a bit to have two wide midfielders rather than wing backs. They won’t defend as much, but we should be dominating possession anyway! It’ll be fine. Plus, this looks more like 3-4-3 on paper, so I will pretend that counts for something despite knowing it absolutely does not.

The next friendly, against another minnow, I tinker a bit. I decide to try a slightly more direct approach to test out one of the other interpretations of Amorim’s style, and it goes a little better with a 4-2 win. But I still don’t like conceding two goals against a small side, and also having such little control of the game as a result of my players regularly gambling on more ambitious longer balls.

The third, against Bayern Munich, we win 3-1. I’m trying not to get too excited because it’s just pre-season, but this is looking promising – this squad is absolutely not good enough to beat Bayern Munich 3-1. I’d tinkered again here, going back to a shorter style but a bit less central so we could use the wing backs a bit more, and this one feels like a winner.

Friendly number four, against Bundesliga strugglers Wolfsburg, brings me right back down to Earth, as we get clearly beaten 2-0. I did say we shouldn’t get too excited, I just didn’t listen to myself.

Finally, with a Community Shield game against Man City, a rapidly building list of injuries (accurate), and a somewhat chastening pre-season run of inconsistency under our belt, it’s time to start the season.

After a lot of tinkering, I decide to, a) not panic and stick to broadly the same tactics, in part because the players really need to start building some familiarity; and b) I settle on my starting 11. Mazraoui fills in for Shaw on the left. Maguire has come into the middle of defence by now and De Ligt pushed out to the right, after a terrible run of games from youngster Yoro (he’s only 17 in this save, and very raw; time to take the lad out of the spotlight for a bit). I’ve pulled in Casemiro next to Ugarte as a deep-lying playmaker to shore up central midfield and avoid overplaying young Mainoo. And I’ve stopped the Libero experiment already, after getting caught out a few too many times on the left. Let’s save the fancy stuff for when we’ve got a bit of momentum.

As an aside: FM has done well to introduce some great rotational play to allow for setups like this, but this one doesn’t quite work. There’s no function to get your central defender to step to the left to fill the left defender’s vacated space when they move forwards as a Libero. Thankfully, there’s a (sort of) workaround anyway. Instead of a left-sided Libero, I use Maguire as a classic ball-playing defender in the middle.

There’s an extra bonus here too. A lot of analysts point out that from goal kicks, Amorim’s back three do something unusual. Typically, in real football, the central defender would go to one side, the wide defender on that side pushes further wide, and the back five sort of shuffles along to look like a typical back four, with one wing back pushed up to the midfield. But often Amorim’s central defender stays in the middle instead, pushing forward a bit. A quirk of Football Manager is that Maguire naturally does this when set up as a ball-playing defender in the middle, so we’ve sort of hacked an Amorim-ism already.

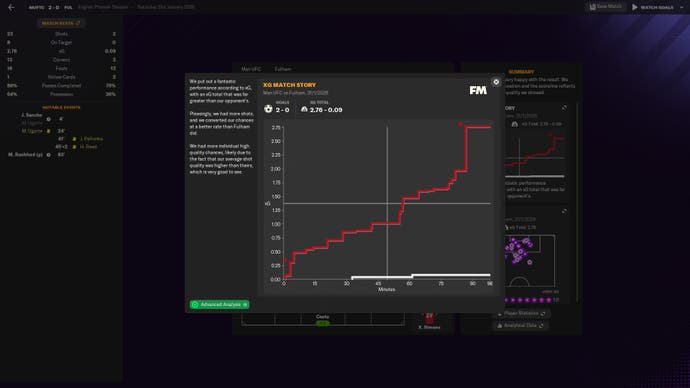

The results are… good?! City are kept largely quiet, with just one big chance, from a highly dubious penalty that Kevin De Bruyne naturally smashes into the net. We win 3-1 and we’re good value for it, well ahead on (non-penalty) xG at the end of the match and also, miraculously, dominating possession against Pep Guardiola’s side. And this game was semi-competitive as well, being the Community Shield. Technically, we’ve just won our first trophy. After a very wobbly pre-season, suddenly things are looking up.

Part 4: The experiment continues to wobble

The first game of the Premier League season, away to Tottenham, we lose 3-1. Despite sticking with the exact same lineup and tactical settings that beat a vastly superior side, we barely scrape two shots on target, for an xG of 0.36 to Spurs’ 2.6, and despite having 63 percent possession for the game we are ultimately played off the park.

It’s too early to panic yet, I tell myself, not entirely believing it. The thing with FM is it takes a lot of time for players to learn tactical systems properly. Teams get a boost to stats like their Vision from getting along well with each other, for instance, while tactical familiarity requires a lot of specific training and game time – more than a few pre-season games can afford. Currently these boys are playing like strangers. True to real life, but Amorim’s got to find a solution to that.

Our next game, barely a few days later, is against Chelsea at home. I schedule some Team Bonding sessions in training and double up on the tactical focuses, but not until after this match will they really start to have an effect. We win 5-0.

I will be honest: right now, I have no idea what’s going on. Why are we easily beating the good sides and struggling against Spurs? This might make sense if, say, I’d gone for the 5-3-1-1 Amorim used against City in real life, as a kind of counter to these high-possession, high-talent sides, but I didn’t. I’m trying to beat these guys at their own game, and I’m winning.

Until I’m not. The season continues like this. Win a game, lose a game, on and on. A loss to Fulham. A win in the Europa League. A loss in the league again.

Meanwhile, most of my players are struggling for any consistent form. Marcus Rashford, one of the best players in the squad on FM but still out of position here, is averaging a match rating of a dreadful 6.3. I’ve got no left wing-backs, and every time I play with a midfielder there instead, like that Garnacho experiment, or Antony, or anyone else who can kick a ball, we get hammered down that side. Against smaller teams, we’re controlling possession. But I’ve realised we’re just getting torn apart on the break ourselves – effectively the plan Amorim used against City in the real world is being used against my virtual Amorim in FM. It’s time for a rethink.

Part 5: Revelation

This is where the first big revelation hits, and it’s really something I should’ve considered earlier. Football Manager tactics are less about setting up in what looks the same as real life, as they are about getting teams to work in the same way as real life. This is the lesson learned from that Maguire trick in keeping him central from goal kicks – just one that took far too long to set in. There are a few tweaks I make which suddenly and quite dramatically work.

One: with high stats for Teamwork and Work Rate, but pretty mediocre attacking ones, Mason Mount’s best role in Football Manager is in central midfield, not attacking midfield, and he immediately scores when playing as a box-to-box midfielder in that new position. Good.

Two: I should really have looked at how Amorim’s in-game Sporting CP play in Football Manager, to see how Sports Interactive’s own scouts have translated his model to the game. And surprise! In FM, they play with two wingers rather than two attacking midfielders. Suddenly I’ve got a role for Marcus Rashford that he actually understands. Using him as an Inside Forward but still giving him specific instructions to stay narrow effectively gets him into the exact same positions as before, only with a role and ‘official’ position that he fully understands.

This also opens up a role for Joshue Zirkzee, who I think would work very well as one of the two attacking midfielders in real life, but can’t play there at all in FM. Instead, I plonk him into the central striker role, rotating Hojlund out for a break, but this time set Zirkzee as a deep-lying forward with a support duty. Zirkzee dropping deep and Rashford darting into the space he vacates is a winning combination, the two combining nicely for a goal.

Three, and really the one that brings it all together: Amorim’s whole thing is adaptability, but as I mentioned earlier, because of how Football Manager works, we’re only playing one quite rigid way.

Until I realise that, actually FM does sort of have an answer for this. I rework our tactics to have a ‘balanced’ passing style rather than short, and more balanced width as well. The thing about these passing style sliders with Football Manager is that it’s easy to fall into reading them as specific parameters for pass lengths that you’re setting your team: setting the slider to short means they will only play short passes; direct, at the other end of the scale, only long ones; balanced only medium-length ones.

But actually, it’s about probability. Balanced doesn’t mean mid-length passes, it means a mixture of passes. This is exactly how Amorim’s side plays – at least from the little I’ve watched, and the awful lot I’ve been told. Sometimes they play short, sometimes they go long, sometimes they do a bit of both. They adopt the approach that helps them beat the opposition at hand. I put all this into practice and what happens?

Four wins on the trot. We’re six points off first place in the league after nine games, comfortably beating opponents on xG, top of our Europa League group – and still playing without a recognised left-back.

How many lessons can we take from this about how Amorim’s Manchester United might play in the real world, then? Probably not many. Football is complicated – even more complicated than Football Manager – and there’s no telling how Amorim might adapt to the Premier League, who might get injured (beyond lots of left backs), and honestly, who he’s even going to pick to play where. A fun twist here: I loaded up a save I had from half-way through my invincibles season, with a stellar squad that, would you believe it, I’d also tinkered with a very similarly 3-4-3 formation with just to mix things up a bit after we won so much.

Short of a left wing back, you say? May I present Theo Hernandez, who gets three assists in his first game. Josko Gvardiol, now at City in the real world, is the perfect left-sided channel defender. Jamal Musiala slots into one of the attacking midfielder roles (sorry Rashford) and some guy called Jude Bellingham takes the box-to-box role in midfield. Ugarte is also here in this save because, I cannot emphasise this enough, Ugarte is a monster in Football Manager – I’d signed him last year for my United before he joined the real one.

There are more experiments and more tinkering. I try using the two deeper midfielders as defensive midfield positions, which works quite nicely. I try going back to wider wingers instead of attacking midfielders, and setting the side up to counter attack. Like most of this whole experiment, mix results continue.

So, not too many lessons beyond real life, beyond “please sign a left wing back Manchester United”. But how many lessons can we take about Football Manager? Actually, for someone who once thought he knew a lot, quite a few.