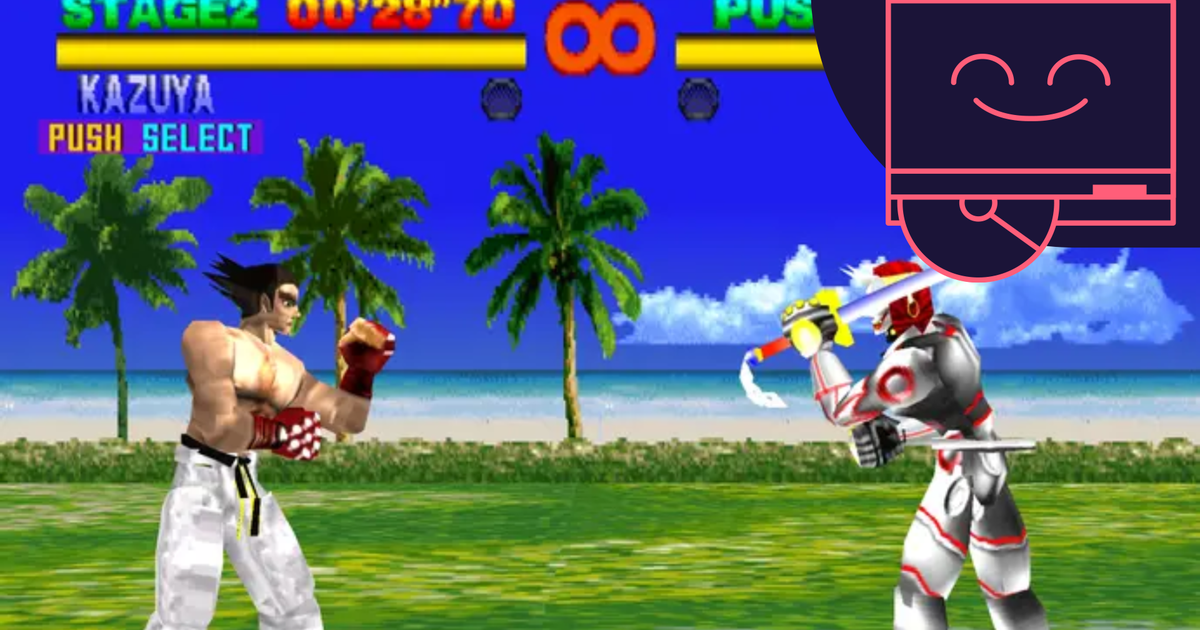

By now, the history of Crash Bandicoot – and the bejorted platformer’s fabled importance to the PlayStation – has been pretty well documented. With Sony’s PlayStation facing off against the Sega Saturn and Nintendo 64, there in the era of Mario and Sonic the debut console-makers felt they badly needed a mascot. And here came Crash, from a small, upstart, still technically independent studio of just a handful of people, and just at the right moment. Shortly before the E3 show of May 1995, Sony was so impressed with Naughty Dog‘s demo it bumped Twisted Metal off its main stand and replaced that game, which it had only just signed, with Crash Bandicoot – pitching up directly across from Nintendo’s booth, where Sony’s rival had come with a new 3D platformer of its own, in Super Mario 64. Shigeru Miyamoto was seen happily giving Crash a whirl at the show, the game sold like gangbusters, and the PS1 lived happily ever after.

The mascot side of things is one factor, undoubtedly. But a less-discussed legacy of Crash is the shift in approaches it marked between the likes of Nintendo and Sony. Where Nintendo opted for something less graphically appealing in Mario 64 (ever wonder why PS1 graphics have had a resurgence in the art styles of today, while nobody’s really trying to look like a game from the N64?), but one where those slightly simpler graphics allowed for more expansive, inventive gameplay. Mario 64 was the game to blow the platformer wide open. Crash Bandicoot, meanwhile, effectively did the opposite.

Cartoony as they are, Crash’s visuals were also richly detailed for the time, packing in the density while keeping the gameplay fairly simple: the developers of Naughty Dog have spoken about their desire at the time to hop onto the growing character action bandwagon and also to effectively recreate a game they’d loved, Donkey Kong Country, in 3D, while jokingly nicknaming the new camera position the “Sonic’s Ass” view. A lot of time has passed between Crash Bandicoot’s release in 1996 and the modern, blockbuster-laden PS4-onwards strategy of Sony today, with a lot of games in between, but there’s also a thread that can be traced through them, from then to now. The split between Mario 64 and Crash Bandicoot effectively marks out a delineation in styles that’s continued for those almost 30 years. A simplified version: on the one hand, an emphasis on mechanical playfulness and invention, at the expense of graphical prowess; on the other, a drive for technical and visual awe, with more familiar, tried-and-tested gameplay to go alongside it. You can see the split, arguably now more than ever, in the first-party games of Nintendo and Sony today.

Obviously that’s slightly over-simplifying. But even beyond that legacy there’s also a third part to Crash’s lasting influence, which I think is also probably the most interesting (and honestly, probably also the most fun). And that legacy is a very strange contradiction: a lot of people love Crash Bandicoot, and a lot of people also think it’s not very good.

For a long time I’ve always approached that as a kind of debate: you love Crash, or you think Crash is bad. More recently I’ve come to realise something very obvious, that I should have realised long ago, which is that actually it is very possible for both of these things to be true. Or maybe more precisely: it’s possible to love a game, to know it’s bad, and to still believe it’s also good. It’s just good in a different kind of way.

Even then it’s tempting to slip into well-worn arguments. It’s good like a popcorn movie is good! It’s low art! It’s ironically good! Tempting, but I don’t think any of these really get it right with Crash. Crash is good and not-so-good at once: not-so-good because, let’s face it, it is a bit derivative – as many of its critics will gladly tell you, it didn’t really do anything special in terms of the actual platforming itself. And it was a bit fiddly – most platformers struggle with floatiness and imprecision; Crash’s almost pixel-perfect platforming, and the requirements of mastering that, is if anything almost too precise. And, as it’s easy to forget with the somewhat smoothed-over remasters, some of its style decisions were very much of the time. These aren’t issues of the “it’s only aiming to be a popcorn flick” variety, where you can dismiss them as part of the charm and move on. They’re just issues.

But! Here’s the magic. There’s another way something can be brilliant – specifically how video games can be brilliant. Scrolling Bluesky the other day – stay with me reader – I saw an extract of an interview with Willem Dafoe. Dafoe’s talking about cinema and the idea of naturalism in acting – this is going to suddenly get very high brow, so again, please stay with me – and he has this to say:

“…we don’t just want to see imitations of life. We want to see something that is beyond that. Cinema is not just about telling stories. Everybody clings to this. Telling stories, telling stories, telling stories! It’s about light. It’s about space. It’s about tone. It’s about colour. It’s about people having experiences in front of you, where, if it’s transparent enough, they can experience it with you. You become them. They become you. That’s the communion. That’s the experience.”

Listen, I warned you.

The point is, because I am forever doomed to have to think about this hobby at all times, always, this got me thinking about video games, and what might be their own form of “communion”. And as I’ve got older and softer and more prone to having the things I loved when I was a child suddenly and rudely turn 20, 25, 30 years old before my eyes, the form of that communion has become just a little more clear.

Think about the popular video games of today – and not just popular in terms of sales, or in terms of critical reception. Popular in terms of what’s talked about, watched, shared as well as played. If a given algorithm’s even vaguely sussed out your interest in video games, chances are that on going anywhere near Tiktok, Instagram, Twitch or YouTube, you’ve probably seen footage of at least one of Chained Together, or the Perfect Pitch filter, or that game where you drive a massive lorry along an impossibly small, clumsily texture-stretched mountain road while a queue of buses comes the other way. Or the The Game of Sisyphus. Or Getting Over It with Bennet Foddy.

These are games that are not, I would say, particularly good. You can probably see where I’m going. They’re not good but they are also so good (some people might contest that with Bennet Foddy’s entry, and that’s fine. Sub in Flappy Bird). They’re games of massive, weird, breakout virality because despite their ostensible rubbishness they are doing what the forgotten category of great game does: making you try, and try, and try. Making you shout, and laugh, and making you fight away your friend’s grasp of the controller for one more turn. And making people who don’t, typically, play video games in the way many people who read a website like Eurogamer play video games feel a sudden compulsion to take part. Mothers and fathers and siblings and that one mate who still thinks it’s immature. You stick Perfect Pitch Filter in front of them after a long, stolid family lunch and watch them barely hit “fah” and fail to hit “soh” – and then fail and fail and fail to hit “soh” – and tell me there isn’t a bit of magic happening here. There isn’t something strangely, mythically, evolutionarily compelling going on, in the same inexplicable, reflexive vein as hiccups and ticklishness and laughter.

This is our communion, here in our weird and undoubtedly immature corner of the art world (that friend was kind of right). I don’t have the words for it – I’m not Willem Dafoe – but I think it’s there. The clue is in the word.

I should probably talk about Crash Bandicoot for a bit. I love this game. I love its sequels, I love Crash Team Racing, I love its jagged edges and searing hot clash of colours and the low quality audio to Crash’s now immortally memed “Woaow!” and most of all, its insufferable, infuriating, impossible [expletive] levels like Road to Nowhere. I love the way its many tombs’ pitch black backgrounds ignite the same eerie call to the void in me as the oldest Mario platformers before it, and how at the same time those games feel a million worlds apart. It’s easy to slip into a bit of mawkishness here, and divert into memories: memories of first consoles, of playing with parents or siblings again, of Christmas, the 90s, games just being on discs, simpler times. Doing so would just slightly miss the point.

It isn’t the memories that make Crash special to so many people, but the things about it that made it memorable. Whatever that communion is, however it’s brought about, in a way that gets people sharing games, watching games, playing them in front of millions online or just passing the pad with that one improbable convert on the sofa at home, Crash Bandicoot had it. If we’re tracing legacies, trace one from that, to the brave new world of video games today. The kids of Roblox and Sisyphus and the rest are becoming detached from graphics, bombast and “telling stories”, rejecting those games and returning, in their own strange, modern ways, to pure play itself, however that’s defined. Follow that thread and like it or not, you’ve got to admit then that Crash was at least a little good. Their good old days will be just like ours.

.png?width=690&quality=75&format=jpg&auto=webp)