Imagine you’re standing in a hallway in a game – what does the scene need in order to make it scary? Should we turn the lights off? Should we have a door where you can’t see what’s behind it, but you can hear something behind it? Should there be a threat somewhere, lurking nearby? Is music important? And at what point is it okay to spring a noisy surprise on the player? In other words, what are the rules of fear?

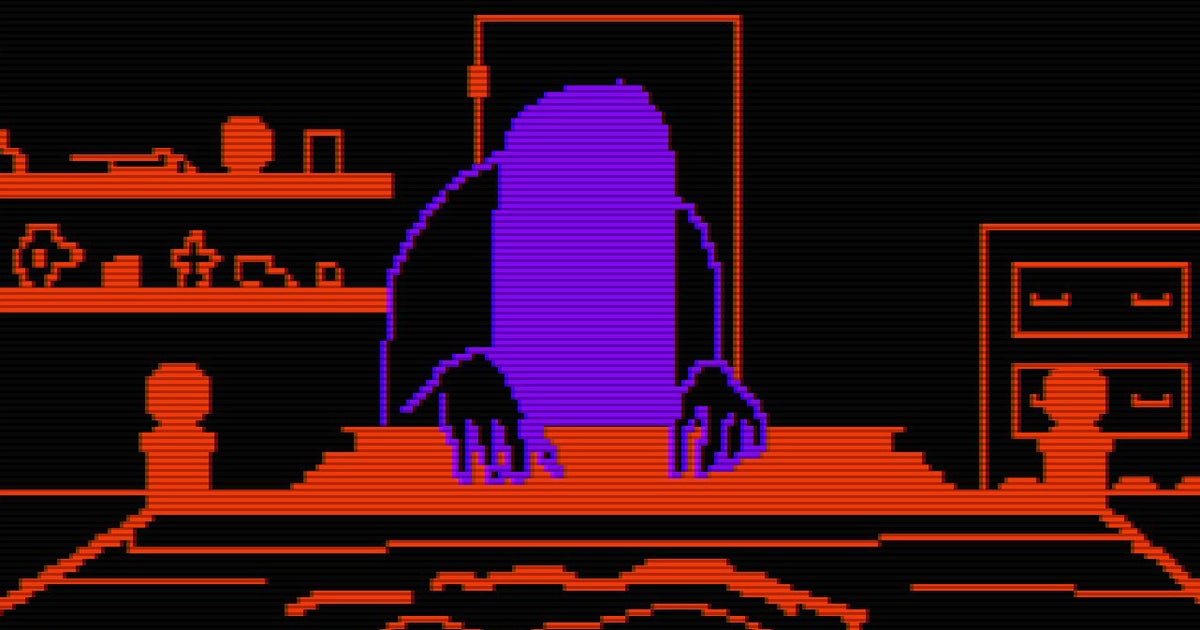

I’ve been thinking about how games scare people ever since lo-fi horror game Faith: The Unholy Trilogy scared me a few years ago, which isn’t a remarkable feat because I’m a scaredy cat. But what surprised me about Faith was how it achieved that feeling, and how little it achieved it with. Here was more or less an 8-bit game, with tiny wriggling sprites and a handful of colours, and it evoked in me the same kind of fear other blockbuster games sometimes struggle to. How was it doing it?

It mystified me enough that I asked Little Nightmares creator Tarsier about fear shortly afterwards, but though the conversation was good, a broader explanation still eluded me. Scaring people remained a magic I couldn’t quite understand, which is when, coincidentally, an answer of sorts came to me.

Magic: just as I’d once asked bright minds from games what magic meant to them, so I would ask scary-game makers how they scared people. Is there a science to it, a formula for fear, and does it change according to the game you’re making? What is the anatomy of a scare?

I sent my ravens out and here are the answers that came cawing back.

Silent Hill creator and Slitterhead director Keiichirō Toyama

Silent Hill is one of the founding series of survival horror, so there are few people who have done more for it, arguably, than Toyama. He also directed the Siren series of horror games, before co-founding studio Bokeh, which recently released Slitterhead.

“In short, I would call it the ‘stimulation of imagination’,” Toyama tells me. “The psychological appeal of horror, I believe, lies in a fundamental desire to collectively identify and overcome threats that surprise and challenge life (and species). Therefore, once something is understood, it may still be a threat, but it no longer evokes fear (as with plagues, for instance).

“Utilising this psychology, I think the key to horror as a creative genre lies in controlling the sense of understanding that is within reach but not quite graspable. A recent work that embodies this mechanism exceptionally well, though not a horror title per se, is Subnautica. It does this very effectively.”

Faith: The Unholy Trilogy creator Mason Smith, AKA Airdorf

Faith is the horror game that prompted this article and lives rent-free in my head, disturbingly. It’s a horror styled like an old Apple 2 game, and though the first Faith game was released in 2017, a third game and trilogy bundle was released in autumn 2022, when I came across it.

“Our reaction to horror is very subjective,” says Smith, “but there are some universal fears I think all humans possess: fear of the unknown, fear of darkness, things like that.

“For me, it’s important to lay down an effective atmosphere, so for games this means creating a setting where the geometry, textures, lighting, soundscape, etc. are ripe for putting the player in the ‘mood’. Once you prime the player psychologically, there are all sorts of fun strategies you as the designer can employ.

“My favourite is something I borrowed from the designers of Dead Space (2008): prime the player to be scared by one specific thing, for example a monster that you see from far away or on a security monitor or on a child’s drawing. The fun part is keeping them in a sense of dread – they know the monster is coming but they don’t know when or where or how. It can be a matter of seconds, minutes or hours before it happens. Tease little visual or audio cues – little bits of environmental storytelling – along the way. The scare – the payoff – can come suddenly in the form of a jump-scare if you want. The problem with a lot of jump-scares is they come without context, but using this method the player is already familiar with the scary thing, so when the scare finally pays off they can go ‘okay, that’s fair’.”

Still Wakes the Deep creative director John McCormack

Still Wakes the Deep is the spooky 1970s oil rig adventure that was released by The Chinese Room this year.

“With Still Wakes the Deep, our intention was to ground the player in realism, comfort and mundanity, then slowly remove the safety nets to expose natural human phobias which would create a general atmosphere where scares would be effective. We give the player safety in numbers through their crewmates, the comfort of the routine of working life and the relative protection of this impossible steel structure against the elements, after which we carefully planned out a cadence of removing those basic protections.

“We take away the crew to give monophobia, then switch off the lights to give us nyctophobia, we force them into unnatural spaces to create claustrophobia as well as vertigo, we compromise the structure of the rig to produce thalassophobia and, of course, we bring aboard a nefarious entity to ramp up the fear of the unknown and death.

“Even with all of these triggers in place, it would only work if the player felt viscerally connected to the main character, to feel everything he feels, to know his past and present and determine his future. Dan Pinchbeck, the lead creative director and writer of the game, provided a fully realised protagonist who reacts authentically to the dangers he is forced to face, and the right mix of script, sound and voice acting was essential in making the player feel everything we wanted them to feel. And because we made the whole experience from this particular character’s perspective, this naturally took away the comfort of knowledge and placed the character in situations where he isn’t sure what to do, what this thing is and if there’s even a chance he’ll make it out alive. All combined, we hoped to create a grounding in character, location and phobias where even the sound of a tin of spam hitting the floor would cause the player to flinch.”

Madison director Alexis Di Stefano

There are people who cite two-person indie horror Madison as one of the scariest games in recent years. It tells the story of a teenage boy with a camera whose pictures connect this world and that of the dead. Say cheese!

“There are many kinds of horror, different ways to create it, and various ways that impact the audience,” director Alexi Di Stefano says. “People with thalassophobia can’t handle games that plunge them into the ocean, just as people with a fear of heights might avoid climbing in VR! For me, something that left a deep mark at a young age was a game called Clock Tower: The Struggle Within. That game introduced me to something new, or at least new to me back then, and it made me feel something I never thought I could experience: fear within my own home.

“The game takes place in an ordinary house (at least in the first chapter) where terrifying events unfold. For example, you might come across a corpse floating in a bathroom tub, or an arm on a tray in the dining room. To nine or 10-year-old Alexis, that experience translated into a terror that lingered every time I walked down the hallways of my own home at night – or entered the bathroom and saw the shower curtain closed! It was terrifying but incredible; it was the push I needed to follow this path which ultimately led me to dedicate myself to horror.

“Homes are supposed to be our sacred places, our refuge, and that game showed me the opposite. Unlike most games of that era, which took place in hard-to-access locations like schools at night or hospitals, Clock Tower: The Struggle Within brought horror into an ordinary, everyday space.

“For me, the perfect scare starts with anticipation”

“When I work on the scripts for my games today, I’m very mindful of how to introduce the specific type of horror I want to convey. It’s not just about jump scares, it’s about crafting an atmosphere that unsettles players even when nothing obvious is happening, or, even more powerful, when players turn their consoles off but still can’t hake the feeling.

“For me, the perfect scare starts with anticipation, followed by tension – so much tension it feels like it will never end. It’s a raw and almost painful kind of tension that frightens more than the scare itself. This buildup is what really gets under players’ skin, making the experience stay with them long after they stop playing.

“I don’t follow a strict formula but I’m aware of a detail that, to me, is far from minor: what isn’t seen is often scarier than what’s placed directly in front of the player. The build-up is key; it’s about keeping players in a constant state of anxiety. In Madison, I play with lighting, pacing and interactivity within the environment to keep them guessing. They know something is coming but not when or how. By crafting a relationship between the player and the environment, every shadow or subtle movement can feel like a potential threat, creating fear through what’s suggested rather than what’s shown.

“A major moment I consider is when the player starts feeling fear, and it’s rarely when they expect it. In my games, I like to create scares that linger in the player’s mind, the kind that make them hesitate before turning a corner or opening a door. To me, the scare isn’t just in the immediate shock, but in the lasting anxiety it leaves behind.

“I’m fully aware that what terrifies one person may not affect another in the same way, but regardless of these differences, we always pour a lot of love and passion into what we create, knowing that people will experience it in diverse ways. If there’s one thing that’s certain, it’s that our bodies – physically and mentally – will unmistakably let us know the exact moment fear begins to take hold and when we start to surrender to it. That’s the magic of horror: it’s personal, visceral, and impossible to ignore.”

Dredge studio co-founder Nadia Thorne

As a horror fishing game, Dredge is unlike many of the other games here, yet it manages to evoke an unsettling and tense atmosphere all the same.

“One thing we observed early on while playtesting Dredge,” Thorne says, “was the power of ‘tell, don’t show’. Even in our early prototype, having characters warn players to return before dark or hint at horrors in the fog had players imagining all sorts of things that could happen to them if they were caught out on the water still when night fell.

“You can’t string players along forever and do need to deliver on the promise of terrifying encounters or you’ll lose their trust, but in Dredge the player’s own mind can be just as suspect as some of our characters.”

Dead by Daylight senior creative director Dave Richard

Dead by Daylight is a four-versus-one multiplayer horror game inspired by slasher films of the ’80s and ’90s, in which you can play as both the killer and the victim. Today, eight years after launch, more than 60 million people have played it and it’s adapted dozens of horror licences from around the world of movies and games.

“Fear is at the basis of what we do, of what Dead by Daylight is and how it came to be,” says Richard. “There are two main facets to fear: being scared and scaring people, and those are the two tenets of Dead by Daylight, which makes it unique in the horror video game universe. In DBD you can feel both helpless and extremely powerful, and both emotions are strong and make for an intense, thrill-seeking playing experience. There are innumerable types of horror – slow burn, psychological, slasher… – and Dead by Daylight delves into all of them.

“For each new chapter we release, we start with a theme,” Richard goes on, “either of horror or a type of experience we want players to feel. From there we elaborate on our vision. The whole DBD team is really passionate and everyone comes up with ideas and concepts throughout the development. Each discipline adds to the horror experience, from the visuals who inspire the audio, to the audio who inspires the VFX. Everything is connected.

“The way we know that we have accomplished our goal starts internally when we run playtests and we hear, or see, our colleagues jump or grunt in disgust – we know we’ve hit our target then. Ultimately fear can be entertaining, and that’s what we want our players to experience.

“There is no secret formula to Dead by Daylight’s success,” Richard adds. “I believe we have been very lucky to create something in which players can act out the fantasy of being the villain in a horror movie or can experience the thrill of being chased, or can just spectate on this very good raw show of humanity and emotions. Our goal is always to surprise, and I think we’ve accomplished that. Fear is the gateway to so many emotions, and we want our players to feel them all.”

Signalis writer/director Yuri Stern

Stern apologies that they didn’t have time to formulate, as they put it, a more satisfying answer, but they did have this to say about five-star banger of a survival horror game, Signalis.

“For Signalis, we focused on horror stemming from oppressive systems, both in gameplay and narrative, rather than direct scares, so the ‘anatomy of a scare’ extended for us into all aspects of the game, including the gameplay systems (restrictive inventory, dwindling resources), world-building and narrative (overbearing bureaucracy, cosmic horror).”

Bloober Team director/designer Wojciech Piejko

Wojciech Piejko worked on Bloober’s memorable sci-fi horror detective game Observer, and its early PlayStation era-inspired survival horror The Medium, and is now co-directing Cronos: The New Dawn, a survival horror set in an alternate reality version of 1980s Poland.

“Our goal at Bloober Team is to create horror experiences that linger in the minds of our players even after they have put down their controllers,” Piejko says. “To achieve this, we need to get into their minds because the scariest things don’t happen on the screen, they are happening in players’ heads. In horror, less is more. The less you know, the less you see and the scarier it becomes. Think of the first Alien movie: it’s good because you can’t see exactly what the Alien looks like so your brain starts to work. The oldest fear in the book starts to haunt you – the fear of the unknown. In my opinion, the key is not to provide too much information to the player and slowly build up the atmosphere, delving into the story while never revealing everything. There are things that should never be explained; isn’t it more interesting and even strangely romantic?

“As the horror creator, you also need to know how to control the tension, and of course, it all depends on the game you are making. Can the player fight the monsters? If so, you need to understand that when combat starts, the player feels relief – the player no longer thinks about what is lurking in the shadows and the survival instinct takes over. The key to success in this case is to create a great atmosphere and build-up before combat encounters begin, or even trick the player into thinking that they will be attacked and then not do it.

“Example scenario: Imagine you are playing a survival-horror game and looking for a key. You enter a new area and hear the rhythmic sound of something hitting the wall. Finally, you see a monster banging its head against the wall. It doesn’t see you; you have already fought this type of monster, and it’s strong and challenging so you sneak behind its back. You search the rooms and find the key, so now it’s time to pass the monster again. On your way back, you hear the banging again but this time, it suddenly stops. You check the corridor and the monster is gone. Where is it – will it jump out at you from another room? This is where the real fear starts.

“Many horror games strongly rely on jump scares, which are often perceived as the cheapest way to scare the audience. However, if done right and not too often, they can serve as a good way to bridge scenes and relieve tension, giving you an opportunity to build it up again. While making The Medium, a game with no combat, we included one big jump scare just to inform players that this type of thing may happen again, so they will be afraid for the rest of the game. To pull off a good jump scare, you need to grab the player’s attention on something else and then suddenly attack. It’s like a magic trick that can be described in three steps:

- The Pledge – The magician shows you a card and hides it in the deck.

- The Turn – The magician lets you check the deck, but you can’t find the card there.

- The Prestige – The magician pulls the card out of your pocket.

“Now let’s translate this to the jumpscare:

- The Pledge – You hear scratching coming from behind the door.

- The Turn – Despite the tension, you enter the room to find out it’s only a rat.

- The Prestige – You turn around to see the monster standing behind you.

“Sometimes, you can use only two steps; the most important thing is to focus the audience on something and then attack when they don’t expect it. Find something that the player does constantly and feels safe about, then use it against them. One of my favourite moments in making Observer was a bug that scared me to death. I was testing one of the levels and when I turned around, I saw the Janitor, who shouldn’t be there – I almost jumped out of my chair. That was a bug that spawned the Janitor in the wrong position, but it was so effective that we used this scenario in a different part of the game.

“PS: Don’t forget about the music or the absence of it – ambience and sound effects are some of the most important ingredients for evoking fear. PPS: Remember that less is more? It also also applies to graphics: darkness is your friend. Add some grain and the shadows will start to move – or did something move in the shadows? I could talk for hours but I need to go back to work on Cronos; I hope it will scare the shit out of you after its release!”

What surprises me about these answers is that I didn’t expect there to be such a close relationship between magic and fear. I’ve set out on two separate occasions to find answers to two seemingly separate topics, but discovered they are, at their foundation, perhaps fundamentally the same. They both revolve around the unknown. Magic is the term we tend to give something we don’t quite know how to explain, when we’re reaching for something our lack of understanding doesn’t let us find. That gap is important; it’s the allure. We hunger to know what’s going on so we’re no longer adrift or unmoored, our mind grasping for any explanation it can hold onto. The door in our imagination opens up and a tornado swirls through, full of anything and everything, fact and fiction, exciting ideas and frightening ones. It’s uncomfortable; we need to know.

It’s this desire Silent Hill’s Keiichirō Toyama references trying to prolong when he talks about “controlling the sense of understanding”. What he’s saying, I think, is that the player should never know, not entirely – the doorway to their imagination should always be open. Bloober’s Wojciech Piejko shares a similar viewpoint, saying, “the less you know, the less you see and the scarier it becomes”, and Madison’s Alexis Di Stefano agrees: “What isn’t seen is often scarier than what’s placed directly in front of the player,” they say. It’s scary because of your imagination: that’s the element that stays with you long after you close the game. Nadia Thorne and the Dredge team realised a similar thing: that it was more effective to hint at horrors than explicitly display them. And while Dead by Daylight seems to take a more direct approach, is it not the unknown behaviour of the player taking on the role of the killer that keeps it feeling so eternally fresh? We don’t know what they’re going to do, we don’t know where they’re going to be, and that unsettles us. It’s as Faith’s Mason Smith says: “There are some universal fears I think all humans possess,” and fear of the unknown is one of them.

After all, what better thing to help scare you than your very own mind?